Two Dimensional Periodic Systems: Part IV

Two Dimensional Plane Groups

As we mentioned before, in two dimensions there are seventeen plane groups, analogous to the 230 space groups in three dimensions. Here we'll talk about these plane groups and look at their allowed Wyckoff positions. Since we're dealing with a two-dimensional system we can draw diagrams that show examples of these groups without having to deal with perspective, peering around the back of the lattice to see what's there, or using 3-d glasses. Along the way we will discuss the concepts that will transfer to three dimensional systems.

We'll group the lattices by Crystal System. This is defined as all lattices with the same holohedry, or rotational symmetry. In two dimensions, the allowed rotations are 360°/n, where $n = 1, 2, 3, 4$ or $6$, (see the Crystallographic Restriction Theorem). Note that an actual crystal structure does not have to have the same rotational symmetry as its underlying lattice -- we'll see below that we can have rectangular structures with only $n=1$ rotational symmetry, even though the holohedry of the rectangular lattice is $n=2$. [As we previously noted, while it is convenient to refer to the holohedry of two-dimensional lattices by the number of allowed rotations, this system will not work in three dimensions and will have to be modified. See (Lax, 1974).2.]

The Parallelogram Crystal System (holohedry = 1)

The simplest system has a unit cell with no symmetry whatsoever. As we found in Part 3, the primitive vectors have the form

Plane Group #1: $p1$

Plane group #1, which has the label $p1$, is the simplest plane group of all: there is only translational symmetry. This is a little tricky: if the lattice vectors obey some of the restrictions listed below (1) then there will be some rotational symmetry. Or the unit cell might contain exactly two identical atoms. In that case there will be an inversion site between the two lattices, which will kick the system up to the $p2$ plane group.

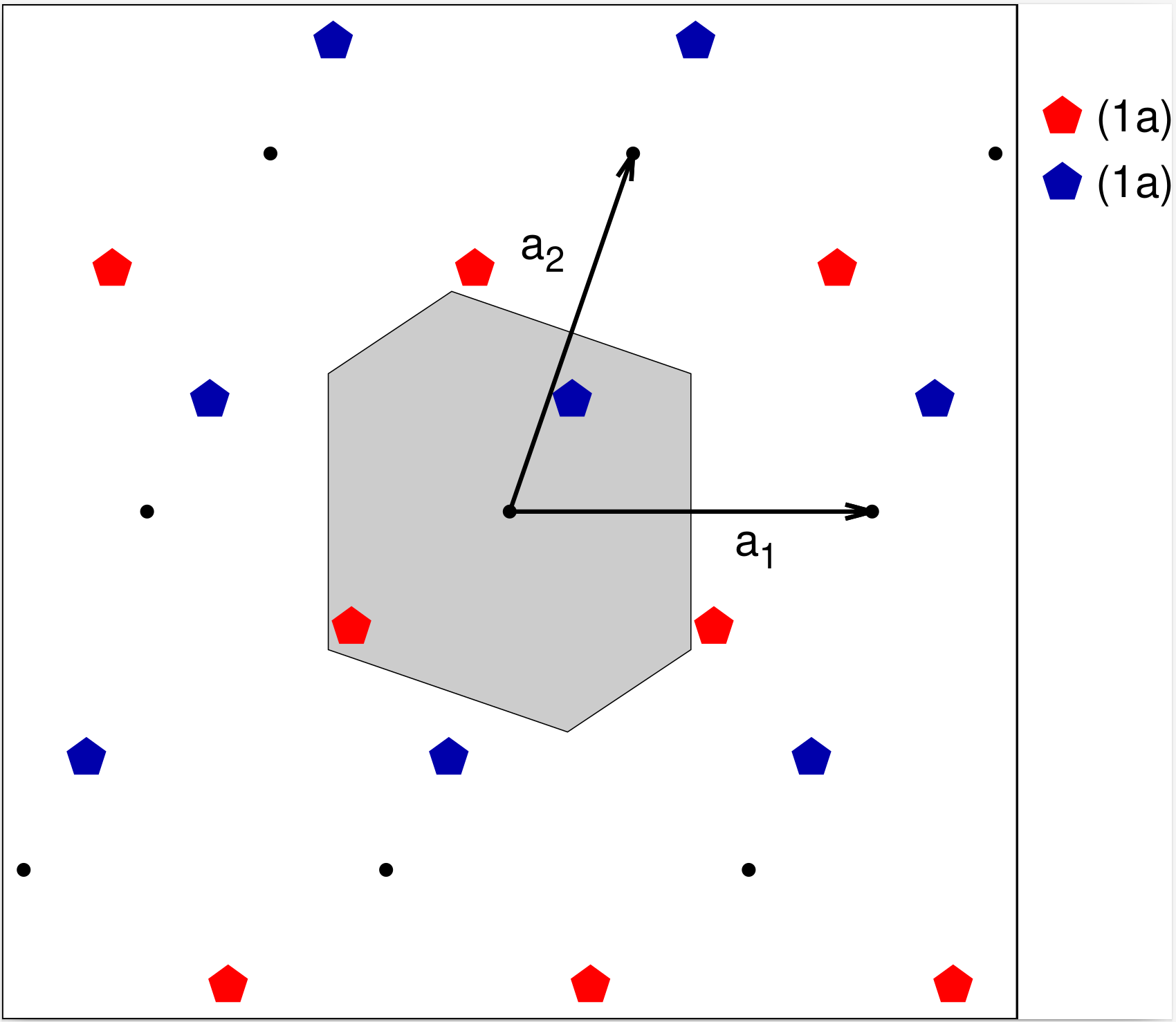

Fig. 1 shows an example of a system that is allowed under these rules. In this case, each unit cell of the system has one red and one blue atom. This is the minimal set of atoms which can have $p1$ symmetry. As we'll see in the next section, if we remove one of the atoms the system has $p2$ symmetry. Otherwise, unless the atoms are place at special points (which we'll cover when we get to $p2$) there is no symmetry in this system other than the translational symmetry given by (1).

A useful way of summarizing the properties of a space group is by listing its Wyckoff positions and their equivalents. Recall that the Wyckoff positions give the positions of an atom as a function of its lattice coordinates relative to the conventional lattice of the structure. If the Wyckoff position is $(x,y)$, the atomic position is

There is only one Wyckoff position for plane group $p1$ as listed in Table 1. From the table we also can see that there is only one atom at a given Wyckoff position. This not true in the general case, as we'll see shortly.

| Label | Lattice Coordinates |

|---|---|

| (1a) | $(x,y)$ |

We cannot be completely arbitrary about the Wyckoff positions if we want to keep the crystal in this lowest symmetry state. For example, if the blue and red atoms were identical, there would be an inversion site halfway between them, and the symmetry would be higher. We'll explain inversion sites and look at that higher symmetry next.

Plane Group # 2: $p2$

Our description of the $p1$ group mentions that we can't have a $p1$ crystal containing exactly two identical atoms. If we did, then we could place the origin between the atoms making their lattice coordinates would become $(x,y)$ and $(-x,-y)$. This property is called inversion, and the origin is the inversion site. If the lattice vectors are given by (1) then the system is part of the plane group $p2$ (#2).

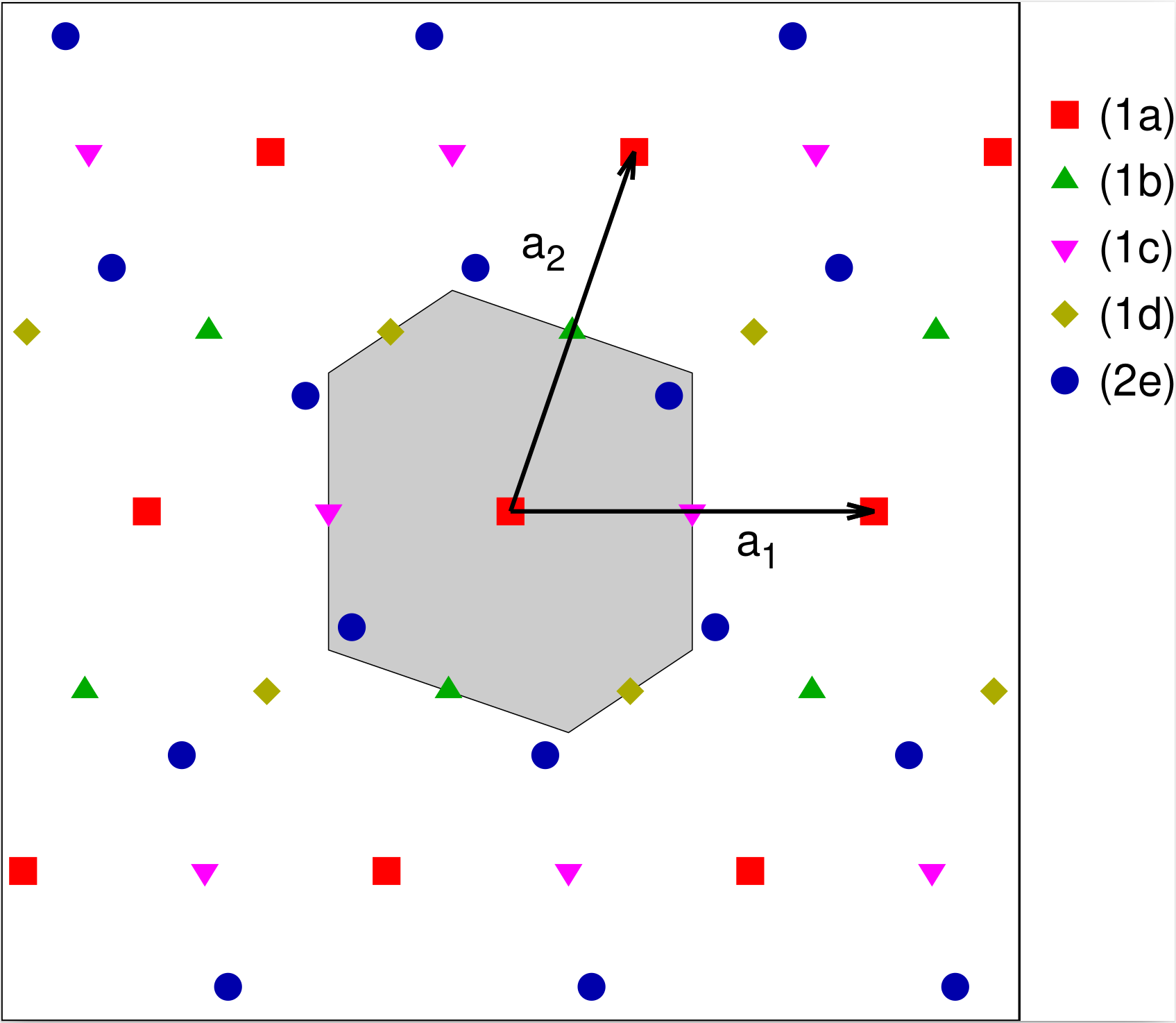

Let's say we have a system where we know that the space group is $p2$ and we find a blue “atom” at $(x,y)$, as in Fig. 2. Then we know that there must be another blue atom at $(-x,-y)$. But what happens if we place a red atom at $(0,0)$? This means a second red atom would appear at $(-0,-0)$ or exactly in the same place. Since in the real world (not our pretend-the-colored-dots-are atoms world) we can't have two atoms on top of each other, we establish a rule that says that if the Wyckoff positions demand that two identical atoms are on top of one other there is really only one atom. In our example that atom is at the origin. The atom still obeys the inversion rule defined above, so its crystal is in the $p2$ plane group. This is why a crystal in the $p1$ plane group must have more than one atom.

Another special case would be to put the atom at a point on a vertex of the Wigner-Seitz polygon, perhaps $(0,1/2)$ (the green triangle in Fig. 2). The second atom then appears at $(0,-1/2)$, but since we are talking about lattice coordinates an atom must also appear at $(0,-1/2)+(0,1)$, or right back where we started. This means that $(0,1/2)$ is also a special case for the $p2$ plane group. There are four of these special cases, which, along with the general Wyckoff position $(x,y) (-x,-y)$ form the irreducible representations of $p2$. All of these are tabulated in Table 2.

| Label | Lattice Coordinates |

|---|---|

| (2e) | $(x,y)$ $(-x,-y)$ |

| (1d) | $(1/2,1/2)$ |

| (1c) | $(1/2,0)$ |

| (1b) | $(0,1/2)$ |

| (1a) | $(0,0)$ |

As we can see from the table, the Wyckoff positions are labeled. These labels consist of a number, representing the number of sites for the Wyckoff position in the conventional cell, followed by a lower case English alphabet letter. The general point always has the highest letter in the alphabet, and is listed first, with the next most populated point the next highest letter, and listed second, and so on. If two or more sites have the same number of sites the points with the lowest site symmetry go first. If all those points have the same site symmetry, as (1a)-(1d) do here, the order is settled by convention.

In this particular case, the (1b), (1c), and (1d) Wyckoff positions are also inversion sites and so have the same site symmetry. We could use any of them as the origin, which would then shift the other coordinates accordingly.

Fig. 2 shows the Wyckoff positions for $p2$. The (1a)-(1d) Wyckoff points are fixed, while the atoms on the (2e) sites can be anywhere in the crystal, so long as every atom at $(x,y)$ has an identical counterpart at $(-x,-y)$.

In the last section we mentioned that if the red and blue atoms in Fig. 1 were on special sites the symmetry of the system would be bumped up to $p2$. Here we can see when this happens: if we move the atoms in Fig. 1 so that the red atom is on the (1a) site and the blue atom is on the (1b) site,(or (1c) or (1d)) then the symmetry becomes $p2$.

Of course in general we can put an atom at (1a), another at (1b), etc., with multiple pairs of atoms on (2e) sites. Fig. 2 shows one possibility out of an infinite number.

The Rectangular Crystal System (holohedry = 2)

Consider the case when a rotation of 180° about the origin does not change the shape of the conventional Wigner-Seitz cell. This can only happen if the cell is rectangular, that is

Plane Group # 3: $p1m1$

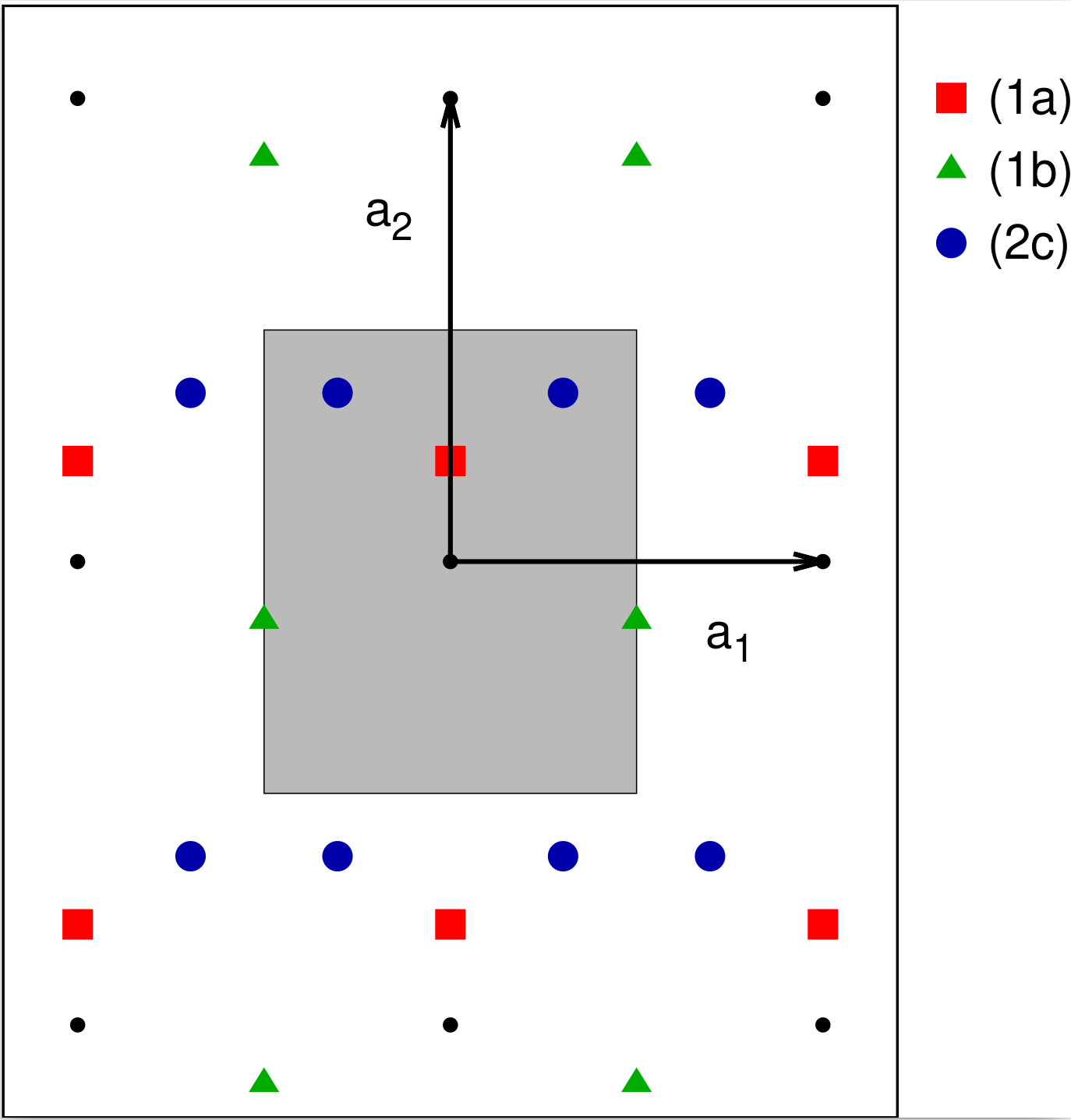

Plane group $p1m1$ #3 is rectangular, with the line $y = 0$ serving as a mirror. That is, if we place an atom at the point $(x,y)$ there must be an identical atom at $(-x,y)$. This leads to the Wyckoff positions shown in Table 3. Possible occupied Wyckoff positions are shown in Fig. 3". Interestingly, this plane group does not require that we fix the origin of the $\hat{y}$-axis. We could easily have chosen it so that the (1a) atom shown was at the origin, or the (1b) atom was at $(1/2,0)$ or even (1/2,1/2). The choice of origin is usually left to the researchers reporting on the structure.

| Label | Lattice Coordinates |

|---|---|

| (2c) | $(x,y)$ $(-x,y)$ |

| (1b) | $(1/2,y)$ |

| (1a) | $(0,y)$ |

One thing to notice is that this structure that crystals with space group $p1m1$ are not invariant with at 180° degree rotation about the origin, even though the holohedry is two. Holohedry is a property of the lattice, in this case the one described by 4), and not the actual crystal structure.

Plane Group # 4: $p1g1$

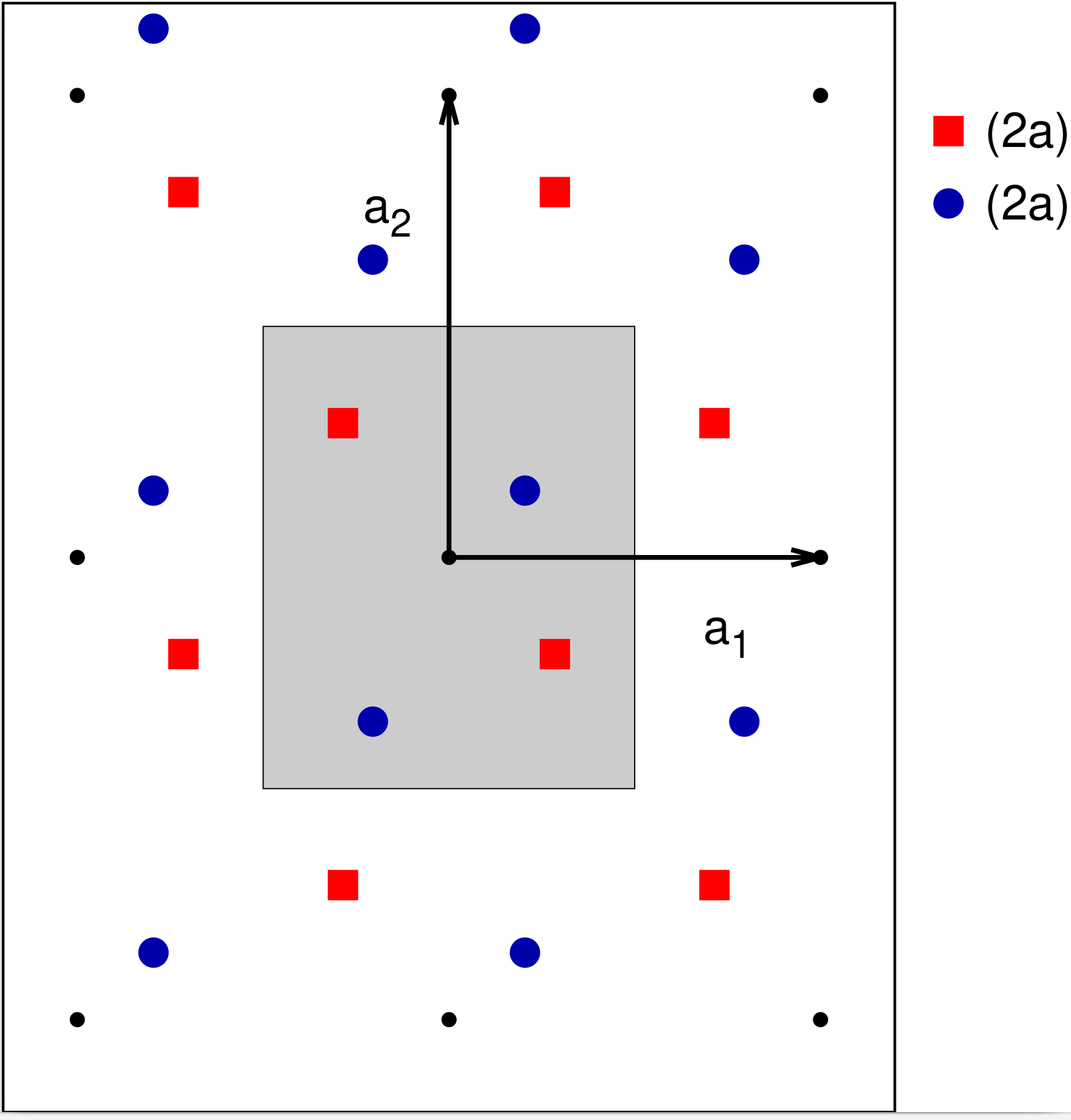

Next let's couple the $x=0$ mirror line in plane group $p1m1$ with a translation, or glide of ½b along that line, so that putting an atom at the point $(x,y)$ implies another atom at the point $(-x,y+1/2)$. This leads to the plane group $p1g1$ #4, shown in Fig. 4. In this case there is only one Wyckoff position, listed in Table 4.

As with $p1m1$, there is no fixed origin for the $\hat{y}$-axis, and the structure is not invariant if we rotate it by 180°.

| Label | Lattice Coordinates |

|---|---|

| (2a) | $(x,y)$ $(-x,y + 1/2)$ |

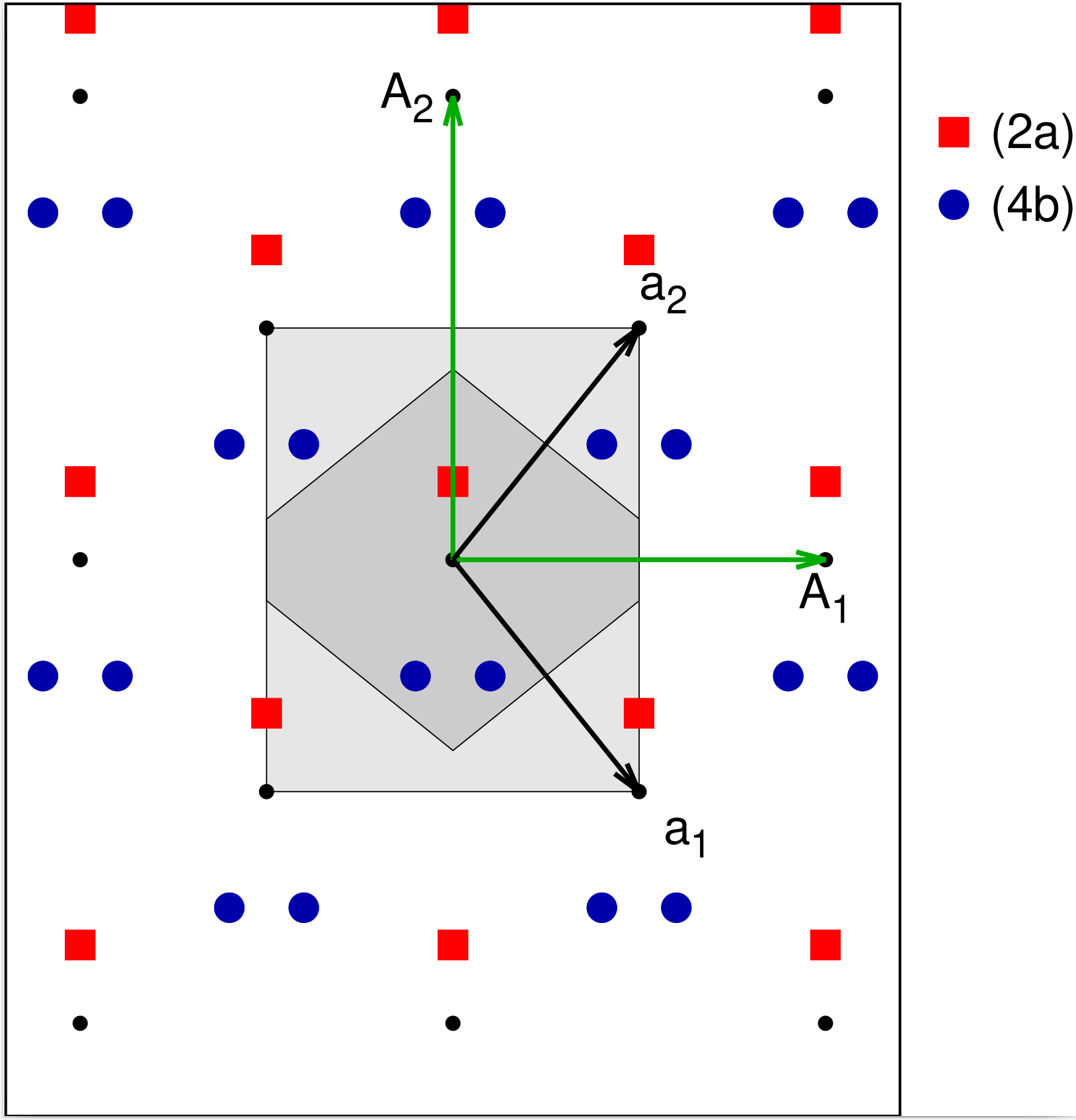

Plane Group #5: $c1m1$

Take a look at either set of the (2c) points in Fig. 3. Suppose we applied a glide translation to both points along the $1/2\,\mathbf{a}_{1} + 1/2\,\mathbf{a}_{2}$ line. Then there would be four of these atoms in the unit cell, with lattice coordinates

It's important to note that both sets of vectors describe the same system, albeit with with different numbers of atoms in the cell. To keep them distinct we call the full rectangular unit cell described by (4) the conventional cell and the smaller lattice described by (6) the primitive cell. In Fig. 5 the conventional Wigner-Seitz unit cell is highlighted in light gray while the primitive cell is the darker hexagon. The plane group is referred to as a centered system, though the reasons won't be immediately obvious until we get to three dimensions, when the question “centered on what?” becomes relevant.

.

Why bother to make this distinction? Why not just use the primitive lattice all the time? The primitive lattice is the basic building block of this structure, but the conventional lattice explicitly shows the holohedry of the system and so puts it in the proper crystal class. From the view of a computational materials physicist the primitive cell is better to use, as it has a smaller number of atoms in the system, and computational effort increases with the cube of the number of atoms. However the description of the lattice given in (6) is not unique. An equally valid set of primitive vectors is

The Wyckoff positions for this plane group are given in Table 5. This table is a bit different than those for the previous ones. First, the coordinates given are for the conventional lattice (4). This avoids the need to specify the actual form of the primitive lattice, be it (6) or (5) or some other form. Second, the lattice coordinates box has an additional line, $(0,0)+ ~ (1/2,1/2)+$. This means that any every coordinate is replicated in the conventional cell, e.g. the existence of an atom at $(x,y)$ implies that there is another atom at $(x+1/2,y+1/2)$ in the conventional cell. Finally, the Wyckoff number indicates the number of atoms in the conventional cell. Thus we have two entries for the (4b) site, giving two positions in the primitive cell (in conventional coordinates), but there are four atoms in the conventional cell.

| Label | Lattice Coordinates |

|---|---|

| $(0,0)+ ~ (1/2,1/2)+$ | |

| (4b) | $(x,y) ~ (-x,y)$ |

| (2a) | $(0,y)$ |

This distinction between primitive and conventional cells will continue into three dimensions in exactly the same way. The only difficulty will be when get to three dimensions and discuss rhombohedral systems, which can be described as their own lattice or as a primitive cell in a hexagonal lattice.

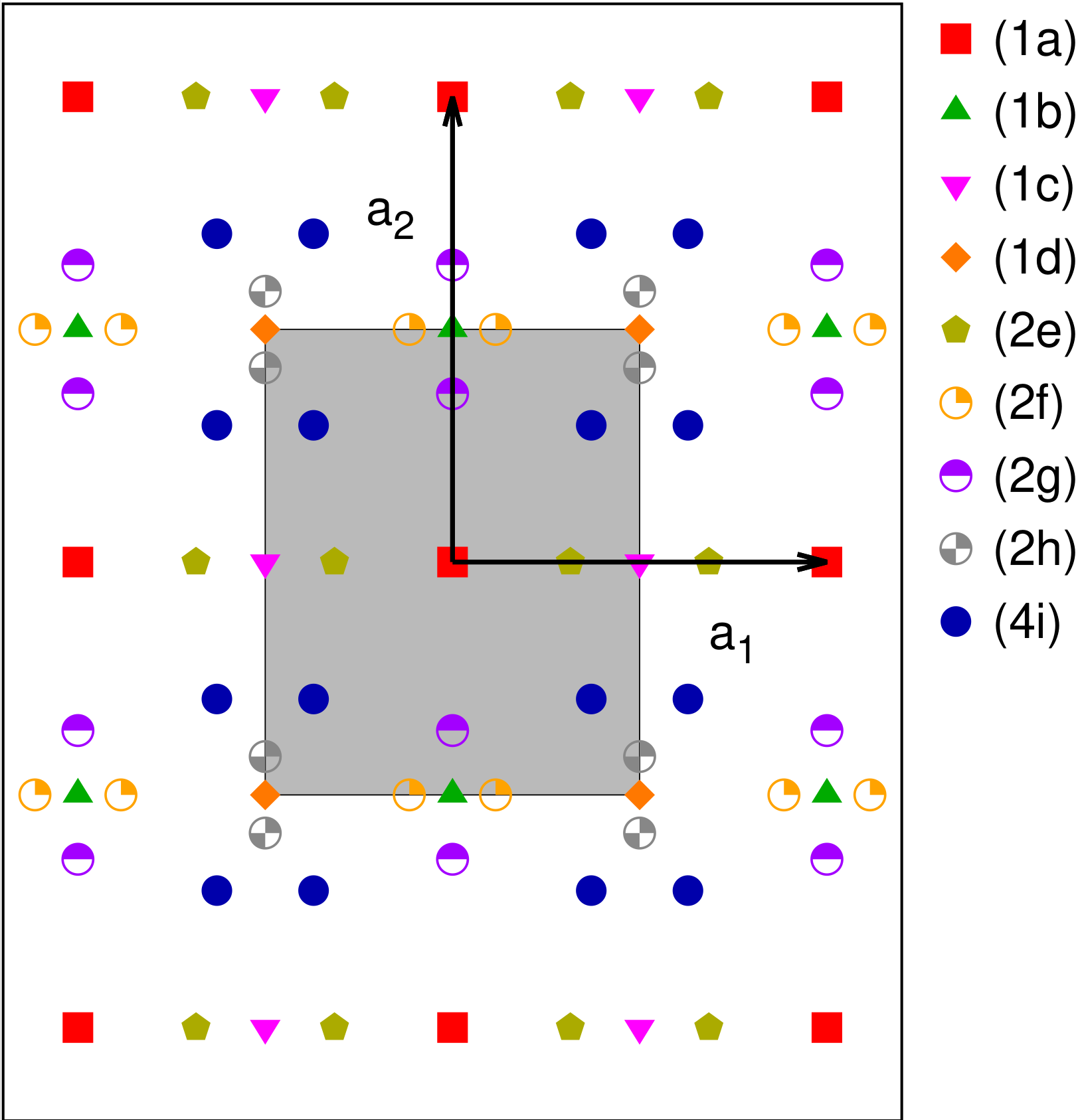

Plane Group # 6: $p2mm$

We now momentarily retreat from centered cells and go back to the $p1m1$ group, but add a mirror line along $x=0$ as well as along $y=0$. This leads to a system that might look like Fig. 6. Since a given point is mirrored across both lines, placing an atom at $(x,y)$ automatically puts another atom at $(-x,-y)$, making the origin an inversion site. In two dimensions this implies that the lattice is invariant with a rotation of 180° about the origin, so this is the first rectangular plane group that has the full holohedry of its crystal system.

The Wyckoff positions for $p2mm$ are given in Table 6. The (1a) through (1d) Wyckoff positions are all at inversion sites, and the (2e) through (2h) positions define the mirror lines. There would seem to be an unusually large number of Wyckoff entries here, because every operation that involves $x$ coordinates is duplicated by a similar operation on $y$ coordinates. This behavior will persist when we look at orthorhombic and tetragonal space groups in three dimensions. One space group, $Pmmm$ #47, has twenty-seven Wyckoff positions, necessitating the use of the label (8A) to describe the general point.

| Label | Lattice Coordinates |

|---|---|

| (4i) | $(x,y)$ $(-x,-y)$ $(-x,y)$ $(x,-y)$ |

| (2h) | $(1/2,y)$ $(1/2,-y)$ |

| (2g) | $(0,y)$ $(0,-y)$ |

| (2f) | $(x,1/2)$ $(-x,1/2)$ |

| (2e) | $(x,0)$ $(-x,0)$ |

| (1d) | $(1/2,1/2)$ |

| (1c) | $(1/2,0)$ |

| (1b) | $(0,1/2)$ |

| (1a) | $(0,0)$ |

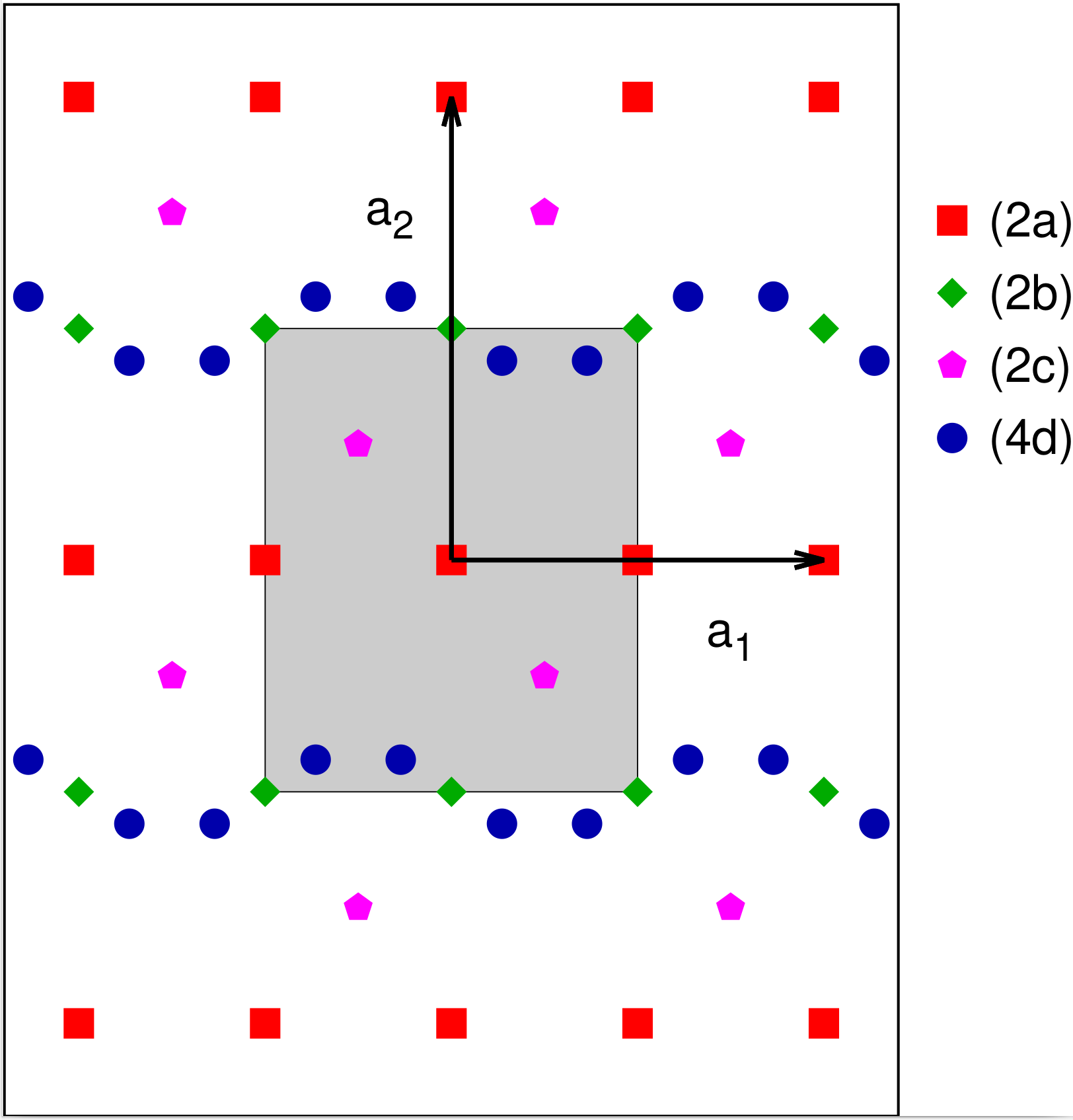

Plane Group #7: $p2mg$

This time we will start with the $p1m1$ plane group, glide by $1/2\,a$ along the $y=0$ line, and add the inversion. The Wyckoff positions for this system are shown in Table 7, and possible Wyckoff positions are shown in Fig 7. Like $p2mm$, this group has the full holohedry of the rectangular system.

| Label | Lattice Coordinates |

|---|---|

| (4d) | $(x,y)$ $(-x,-y)$ $(-x+1/2,y)$ $(x+1/2,-y)$ |

| (2c) | $(1/4,y)$ $(3/4,-y)$ |

| (2b) | $(0,1/2)$ $(1/2,1/2)$ |

| (2a) | $(0,0)$ $(1/2,0)$ |

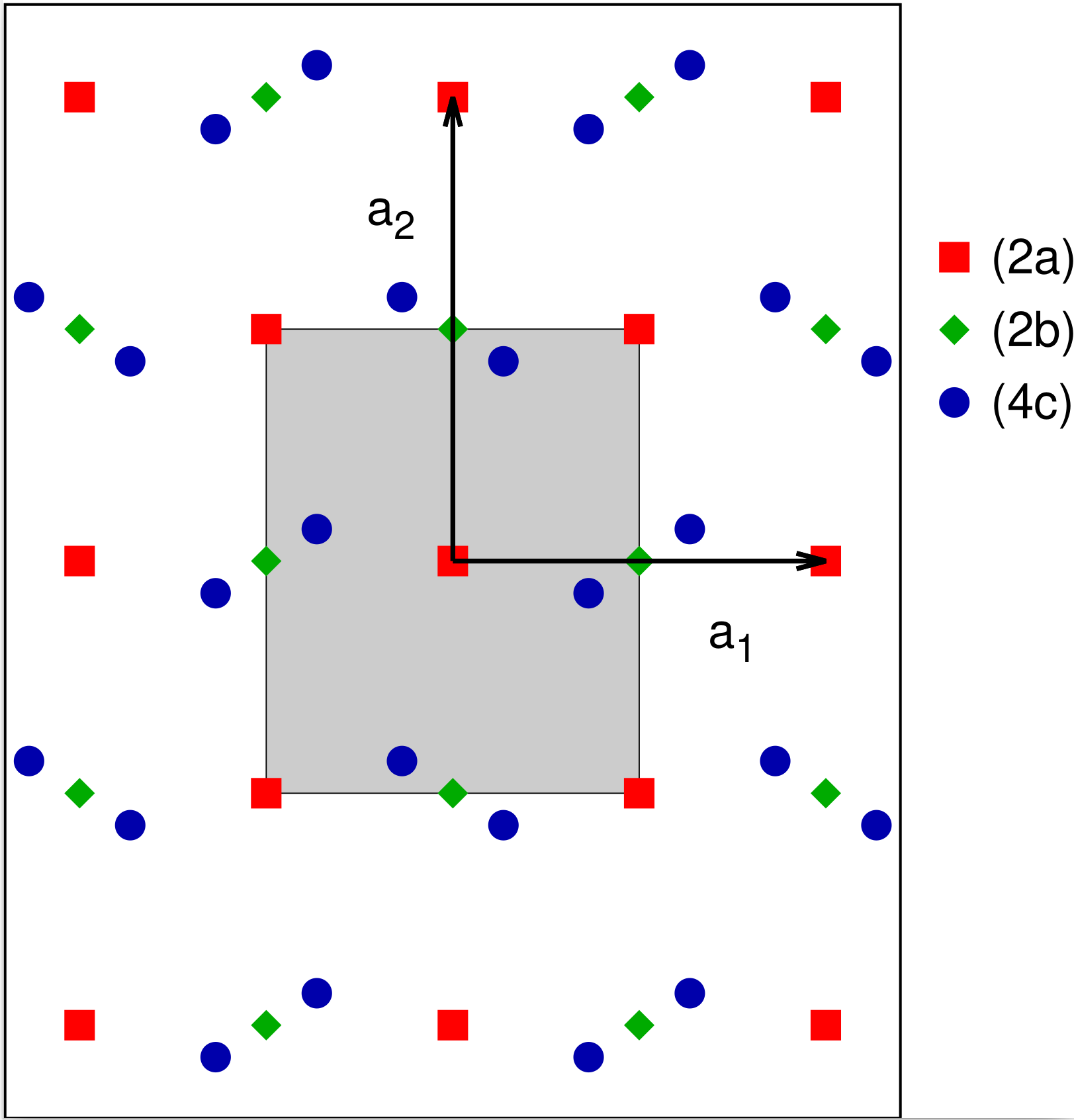

Plane Group #8: $p2gg$

This plane group is constructed by using to mirror+glide operations along both axes and adding the inversion. A structure with this symmetry is shown in Fig. 8 and the Wyckoff positions are given in Table 8. As with all rectangular groups with an inversion site the system has the full holohedry of the rectangular lattice.

| Label | Lattice Coordinates |

|---|---|

| (4c) | $(x,y)$ $(-x,-y)$ $(-x+1/2,y+1/2)$ $(x+1/2,-y+1/2)$ |

| (2b) | $(1/2,0)$ $(0,1/2)$ |

| (2a) | $(0,0)$ $(1/2,1/2)$ |

Plane Group #9: $c2mm$

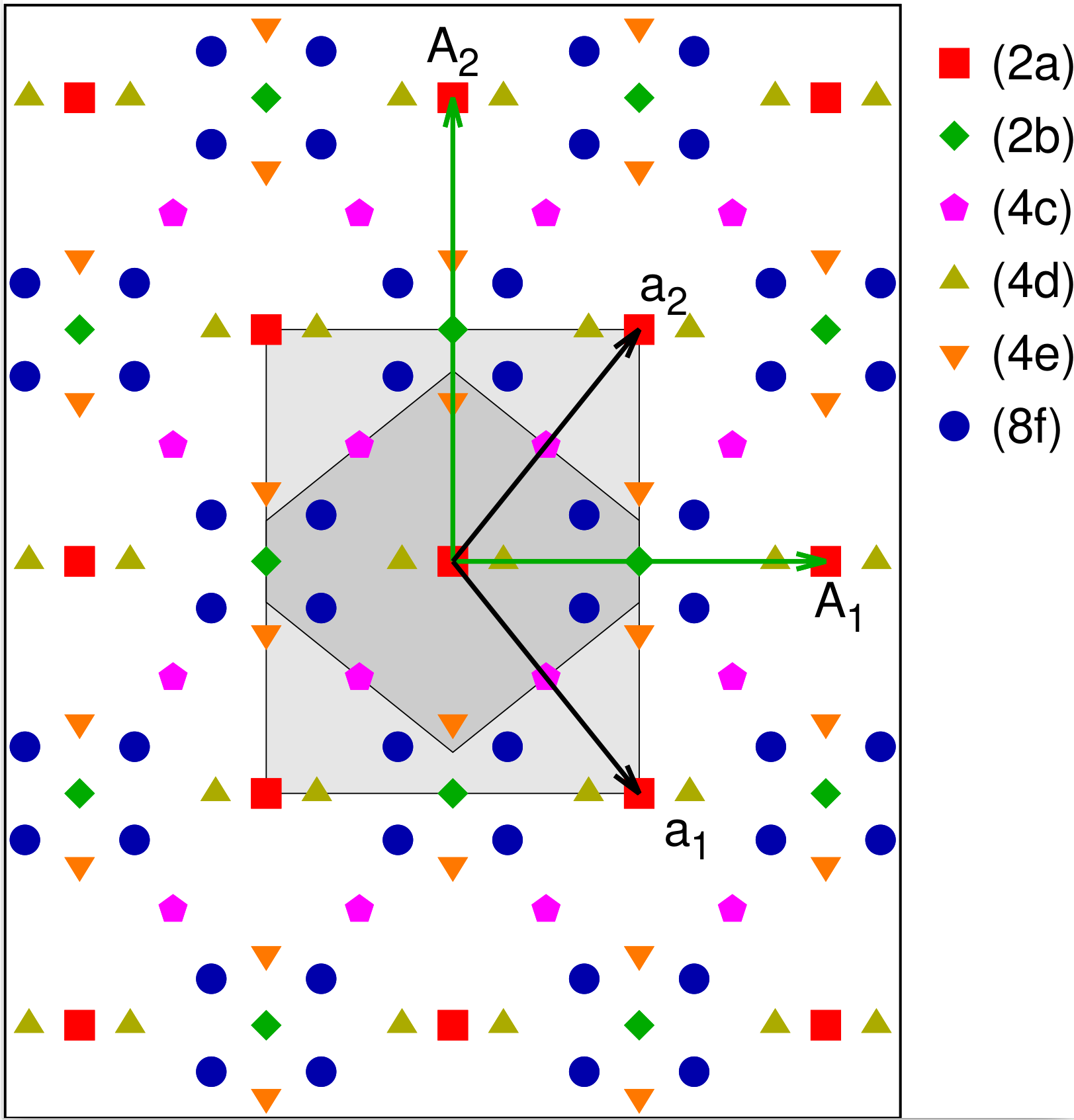

If we add $(1/2,1/2)$ translations to plane group $p2mm$ we obtain the centered plane group $c2mm$. A sketch of a crystal with $p2mm$ symmetry is shown in Fig 9., and the Wyckoff positions are given in Table 9. See plane group $c1m1$ for a discussion of the difference between the primitive and conventional lattices for this system.

Table 9: Wyckoff positions for plane group $c2mm$ (#9). The $(0,0)+ ~ (1/2,1/2)+$ is a reminder that each atomic position $(x,y)$ given in the table has a counterpart in the conventional lattice at $(x+1/2,y+1/2)$.

| Label | Lattice Coordinates |

|---|---|

| $(0,0)+ ~ (1/2,1/2)+$ | |

| (8f) | $(x,y)$ $(-x,-y)$ $(-x,y)$ $(x,-y)$ |

| (4e) | $(0,y)$ $(0,-y)$ |

| (4d) | $(x,0)$ $(-x,0)$ |

| (4c) | $(1/4,1/4)$ $(3/4,1/4)$ |

| (2b) | $(0,1/2)$ |

| (2a) | $(0,0)$ |

The Square Crystal System (holohedry = 4)†

As you might imagine, a square lattice is just a rectangular lattice with equal sides, e.g.,

All plane groups (not just the lattices) in this system have holohedry 4, which means that they all have an inversion site at the origin. If a crystal structure does not have a four-fold rotation axis, even if the primitive cell is square, its symmetry reverts to one of the structures in the rectangular system.

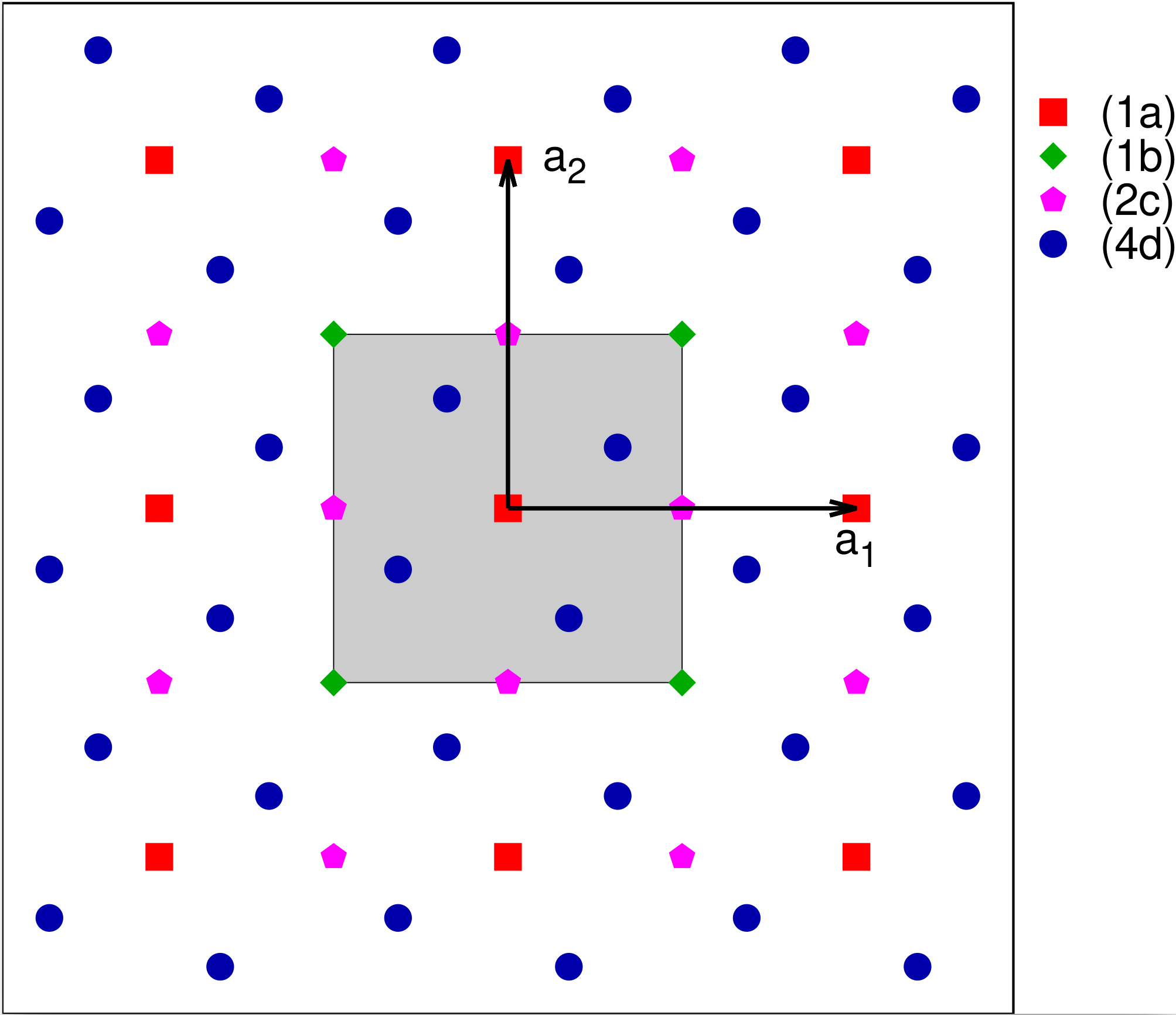

Plane Group # 10: $p4$

This is the simplest of the square system plane groups. The only operation is the 4-fold rotation about the origin. A square $p4$ crystal is shown in Fig. 10, and the Wyckoff positions are given in Table 4.

| Label | Lattice Coordinates |

|---|---|

| (4d) | $(x,y)$ $(-x,-y)$ $(-y,x)$ $(y,-x)$ |

| (2c) | $(1/2,0)$ $(0,1/2)$ |

| (1b) | $(1/2,1/2)$ |

| (1a) | $(0,0)$ |

What happens if there is no inversion, say just a mirror plane $(x,y) (-x,y)$? Then we (mumble) ignore the fact that we have a square lattice and reassign the system to $p1m1$. If this seems a little arbitrary, in practice if a lattice does not have a 4-fold rotation axis it is unlikely that the system will settle in a position where $b$ is exactly equal to $a$, so the question never comes up.

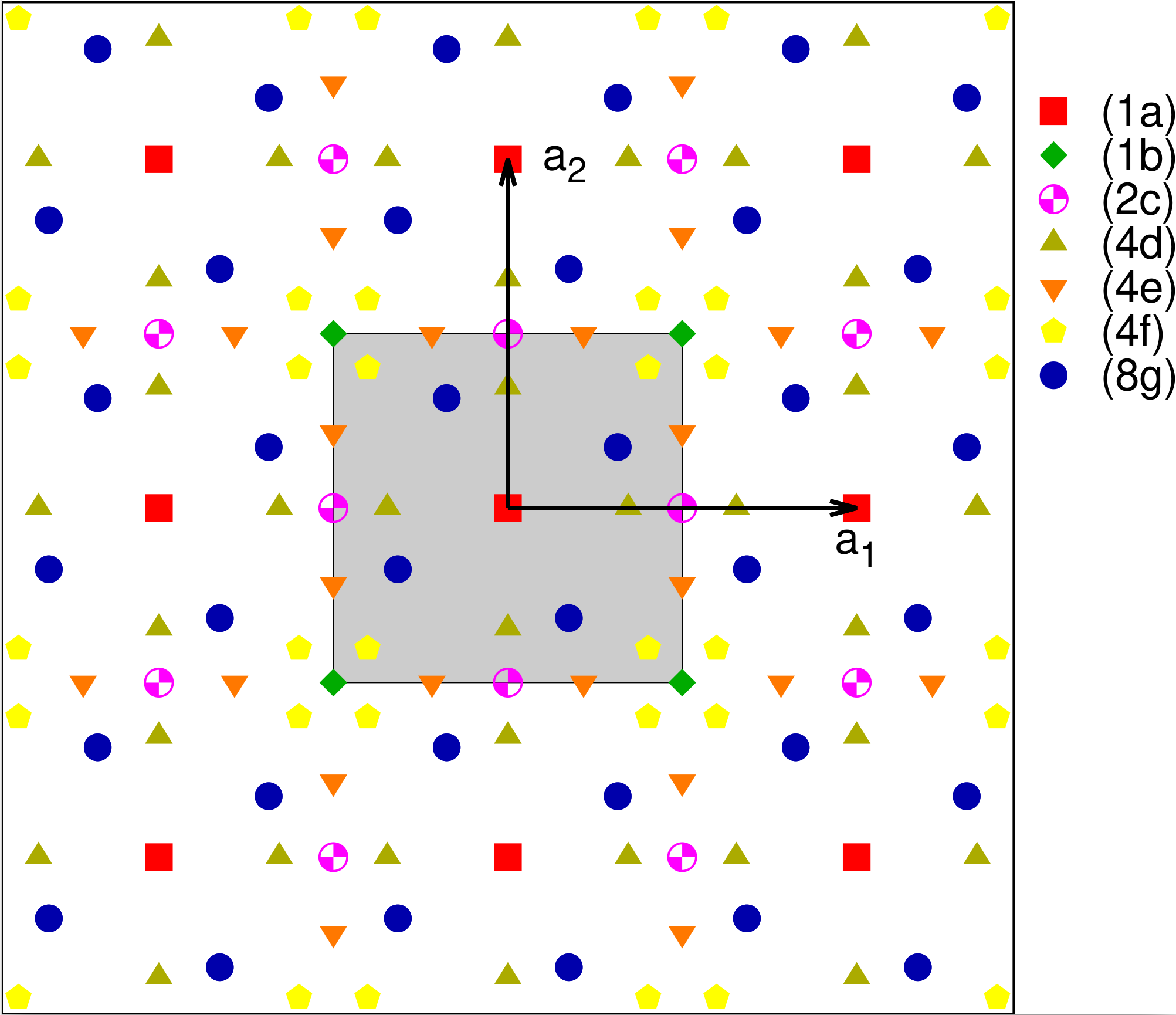

Plane Group #11: $p4mm$

We can add a mirror line along $x=0$ to $p4$, but the rotational symmetry then requires that there be another mirror line along $y=0$. A crystal in the resulting $p4mm$ group is shown in Fig. 11. The Wyckoff positions are given in Table 11. In previous plane groups we only got a new Wyckoff position if $x$ or $y$ had a fixed value like zero, one-half, or one. In this space group we see an new possibility: if $y = x$ the atoms on the (8g) site collapse to only four atoms, the (4f) Wyckoff position. This kind of behavior is also quite common in three dimensional systems.

| Label | Lattice Coordinates |

|---|---|

| (8g) | $(x,y)$ $(-x,-y)$ $(-y,x)$

$(y,-x)$ $(-x,y)$ $(x,-y)$ $(y,x)$ $(-y,-x)$ |

| (4f) | $(x,x)$ $(-x,-x)$ $(-x,x)$ $(x,-x)$ |

| (4e) | $(x,1/2)$ $(-x,1/2)$ $(1/2,x)$ $(1/2,-x)$ |

| (4d) | $(x,0)$ $(-x,0)$ $(0,x)$ $(0,-x)$ |

| (2c) | $(1/2,0)$ $(0,1/2)$ |

| (1b) | $(1/2,1/2)$ |

| (1a) | $(0,0)$ |

You have probably noticed that the (1a), (1b), and (2c) Wyckoff positions are the same for plane groups $p4$ and and $p4mm$. If atoms are only placed on these sites then we could in principle describe this structure as being in either group, but it is customary to use the group with higher symmetry, in this case $p4mm$.

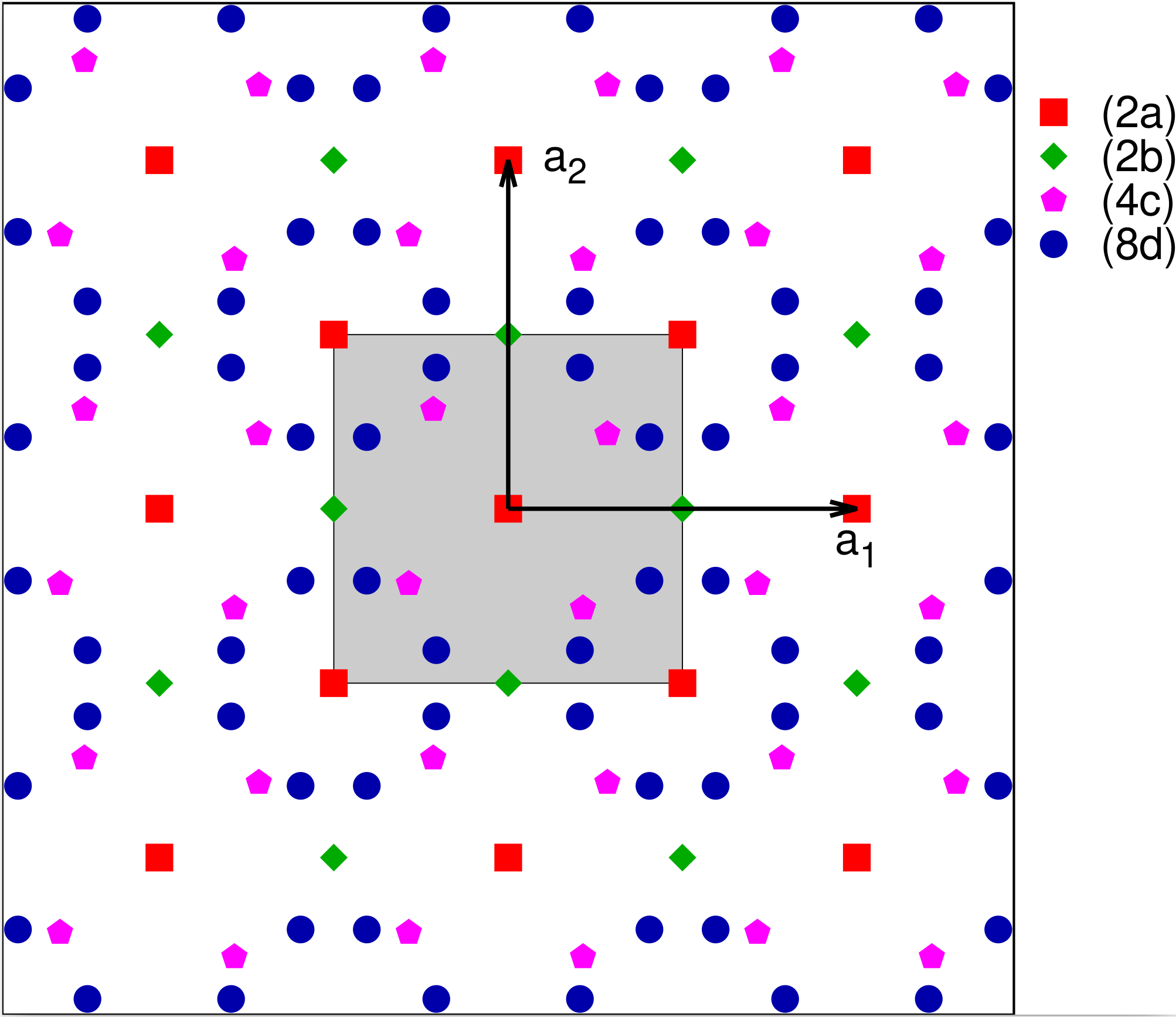

Plane Group #12: $p4gm$

If we start with the rectangular $p2gg$ system, set $b = a$, and enforce the 4-fold rotation of a square group we obtain plane group $p4gm$. This is shown in Fig. 12 with the Wyckoff positions given in Table 12. As with $p4/p4mm$, the astute reader will have noticed that the (2b) site has the same Wyckoff positions as the (2c) site in $p4$ and $p4mm$. Again the rule then is to designate the system as being in the plane group with higher symmetry. This is essentially a tie between $p4mm$ and $p4gm$. Our inclination is to use $p4mm$, as it does not have any translations in the Wyckoff operations, making it the “simpler” group.

| Label | Lattice Coordinates |

|---|---|

| (8d) | $(x,y)$ $(-x,-y)$ $(-y,x)$

$(y,-x)$

$(-x+1/2,y+1/2)$ $(x+1/2,-y+1/2)$ $(y+1/2,x+1/2)$ $(-y+1/2,-x+1/2)$ |

| (4c) | $(x,x+1/2)$ $(-x,-x+1/2)$ $(-x+1/2,x)$ $(x+1/2,-x)$ |

| (2b) | $(1/2,0)$ $(0,1/2)$ |

| (2a) | $(0,0)$ $(1/2,1/2)$ |

The Trigonal Crystal System (holohedry = 3)

Logically this section should go before the square system, which has holohedry 4, but since the trigonal and hexagonal systems are closely related it was decided long ago to put them together on the list.

Both the trigonal and hexagonal systems have the same primitive vectors. These can be derived from the centered rectangular system (6) by setting $b = a/\sqrt{3}$. The standard choice for the primitive vectors of both systems is then

Alternatively we could start the alternative primitive vectors (8) and write

In the following it is important to remember that coordinate pairs such as $(x,y)$ refer to the lattice coordinates of the point rather than its Cartesian coordinates. That is,

Finally, even though we can consider this lattice as a special case of the centered rectangular lattice (6), we will follow usual practice and consider the lattice described by (10) or (11) to be both the primitive and conventional lattice of the system.

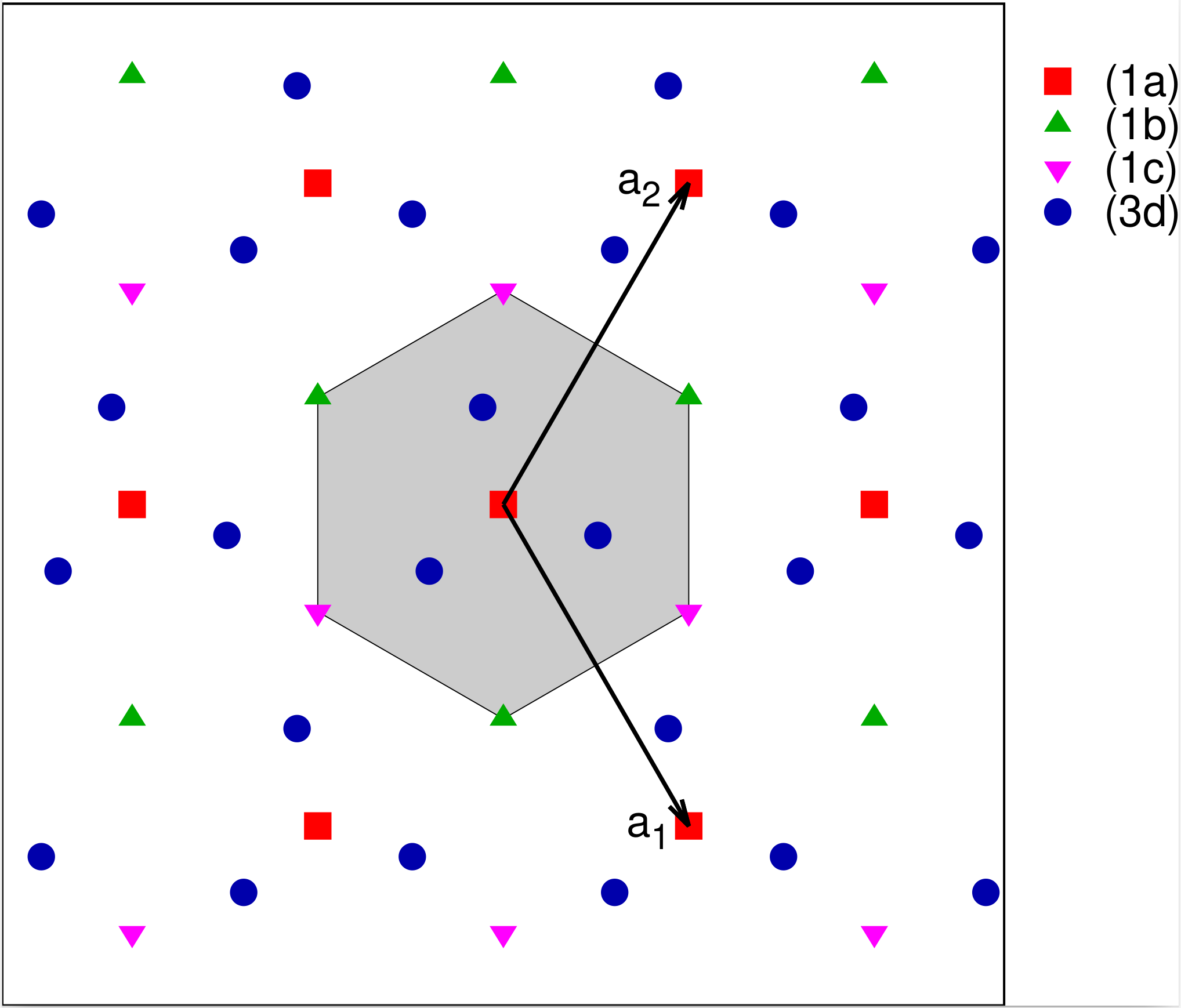

Plane Group #13: $p3$

This is the simplest trigonal group. If an atom exists at a point $(x,y)$ then it has duplicates generated by 120° and 240° rotations about the origin. The group has three Wyckoff positions other than the general position, as shown in Fig. 13 and Table 13. These correspond the the origin (1a) and the vertices of the Wigner-Seitz cell, (1b) and (1c).

| Label | Lattice Coordinates |

|---|---|

| (3d) | $(x,y)$ $(-y,x-y)$ $(-x+y,-x)$ |

| (1c) | $(2/3,1/3)$ |

| (1b) | $(1/3,2/3)$ |

| (1a) | $(0,0)$ |

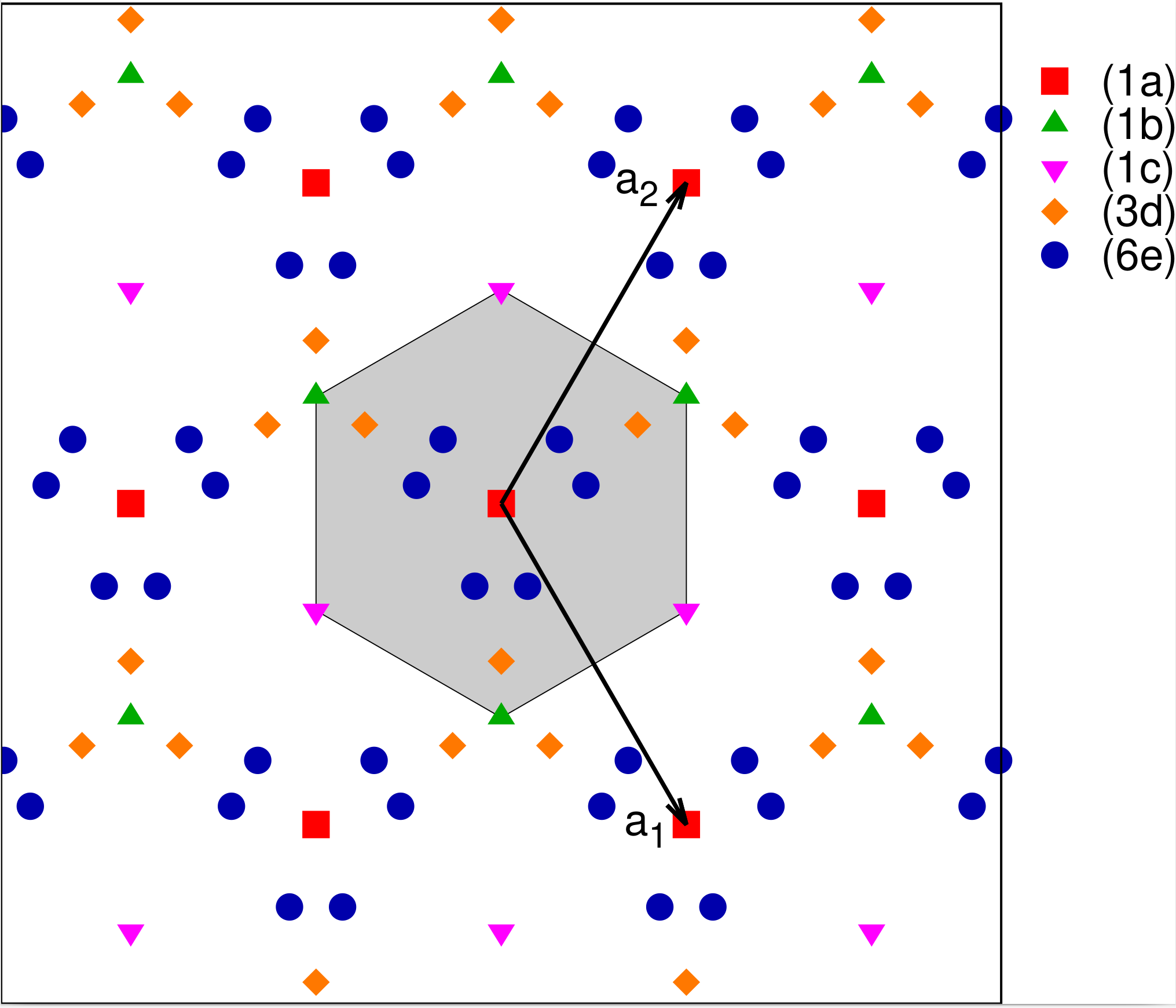

Plane Group #14: $p3m1$

Now let us add a mirror line along the Cartesian $\hat{y}$-axis (not the coordinate $x=0$ line). In lattice coordinates this can be represented by $(x,y) \rightarrow (-y,-x)$. This produces plane group $p3m1$. A sample structure is shown in Fig. 14 and the Wyckoff positions are given in Table 14.

The (1a), (1b) and (1c) Wyckoff positions are the same here as they are for plane group $p3$. Since $p3m1$ has more symmetry operations we would put a crystal with atoms on the (1a), (1b) and/or (1c) sites into $p3m1$.

| Label | Lattice Coordinates |

|---|---|

| (6e) | $(x,y)$ $(-y,x-y)$ $(-x+y,-x)$

$(-y,-x)$ $(-x+y,y)$ $(x,x-y)$ |

| (3d) | $(x,-x)$ $(x,2x)$ $(-2x,-x)$ |

| (1c) | $(2/3,1/3)$ |

| (1b) | $(1/3,2/3)$ |

| (1a) | $(0,0)$ |

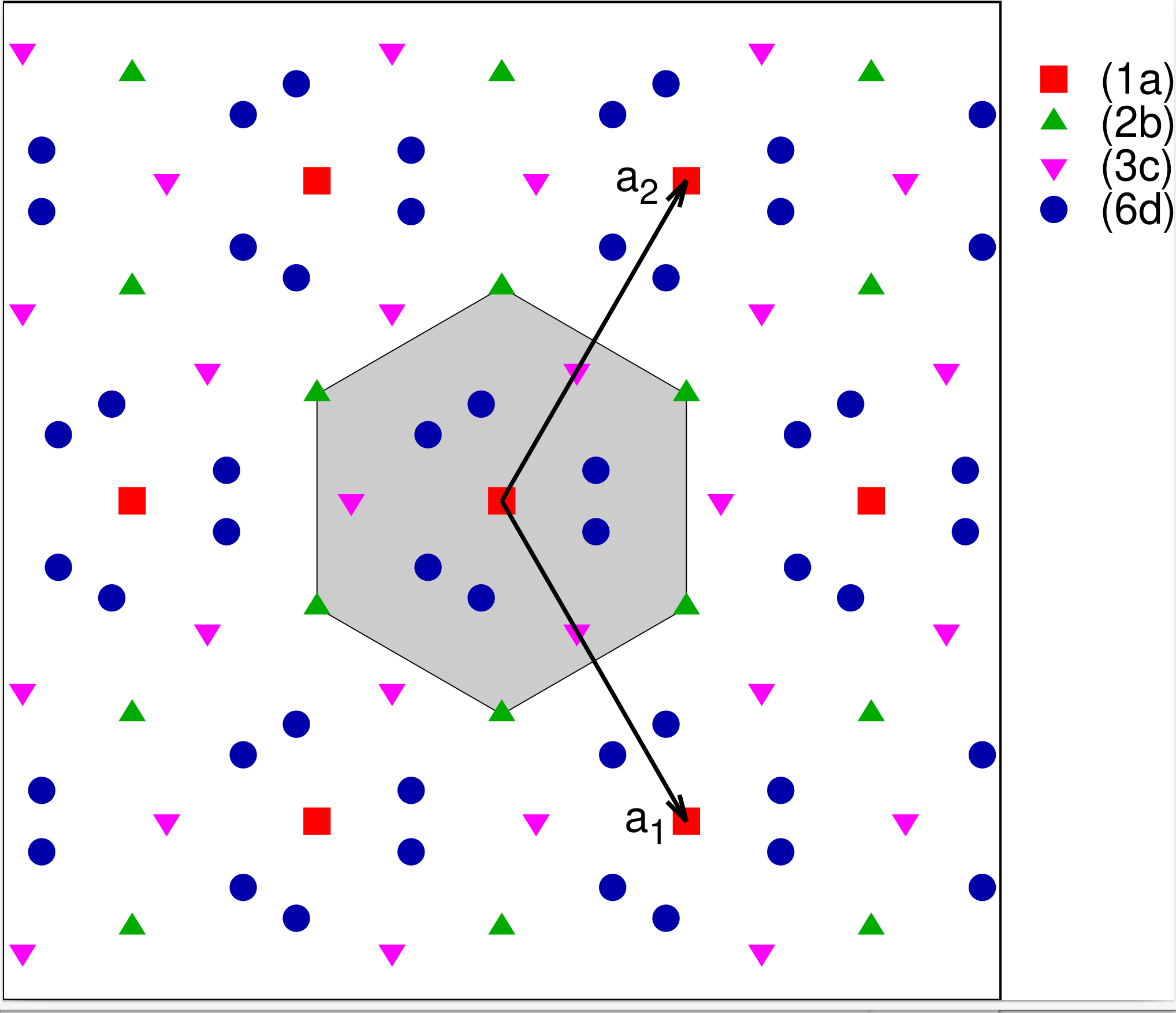

Plane Group #15: $p31m$

The final trigonal group, $p31m$, is much like $p3m1$, except that the mirror line is along the Cartesian $\hat{x}$-axis rather than the Cartesian $\hat{y}$-axis. In lattice coordinates this corresponds to $(x,y) \rightarrow (y,x)$. This leads to the crystal shown in Fig. 15 with the Wyckoff positions given in Table 15.

| Label | Lattice Coordinates |

|---|---|

| (6d) | $(x,y)$ $(-y,x-y)$ $(-x+y,-x)$

$(y,x)$ $(x-y,-y)$ $(-x,-x+y)$ |

| (3c) | $(x,0)$ $(0,x)$ $(-x,-x)$ |

| (2b) | $(1/3,2/3)$ $(2/3,1/3)$ |

| (1a) | $(0,0)$ |

If we glance at Fig. 14 and Fig. 15 we might think that the two groups are essentially the same, but in $p3m1$ the mirror place passes through the vertices of the Wigner-Seitz cell, while in $p31m$ it passes through the mid-points. One of the consequences is that the points $(1/3,2/3)$ and $(2/3,1/3)$ are distinct Wyckoff positions in $p3m1$, but belong to the same position in $p31m$.

The Hexagonal Crystal System (holohedry = 6)

The final crystal system is the full hexagonal lattice, with a 6-fold rotation axis. Since one of those rotations is 180° both of the plane groups in this system will have the inversion site.

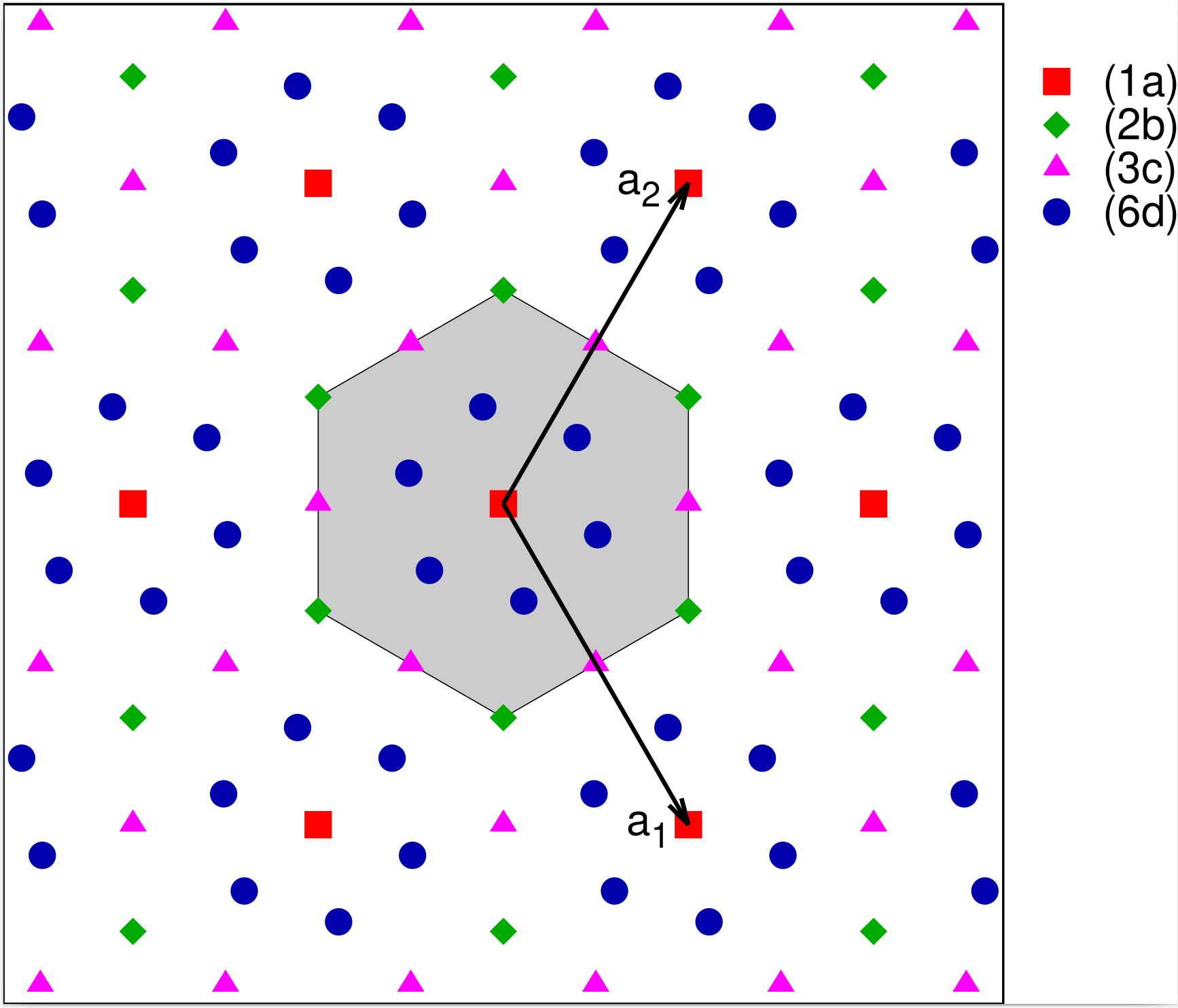

Plane Group #16: $p6$

The only generators for the $p6$ space group are the six rotations, 0°, 60°, 120°, 180°, 240°, and 300°. A crystal with $p6$ symmetry is shown in Fig. 16, and the Wyckoff positions are given in Table 16.

| Label | Lattice Coordinates |

|---|---|

| (6d) | $(x,y)$ $(-y,x-y)$ $(-x+y,-x)$

$(-x,-y)$ $(y,-x+y)$ $(x-y,x)$ |

| (3c) | $(1/2,0)$ $(0,1/2)$ $(1/2,1/2)$ |

| (2b) | $(1/3,2/3)$ $(2/3,1/3)$ |

| (1a) | $(0,0)$ |

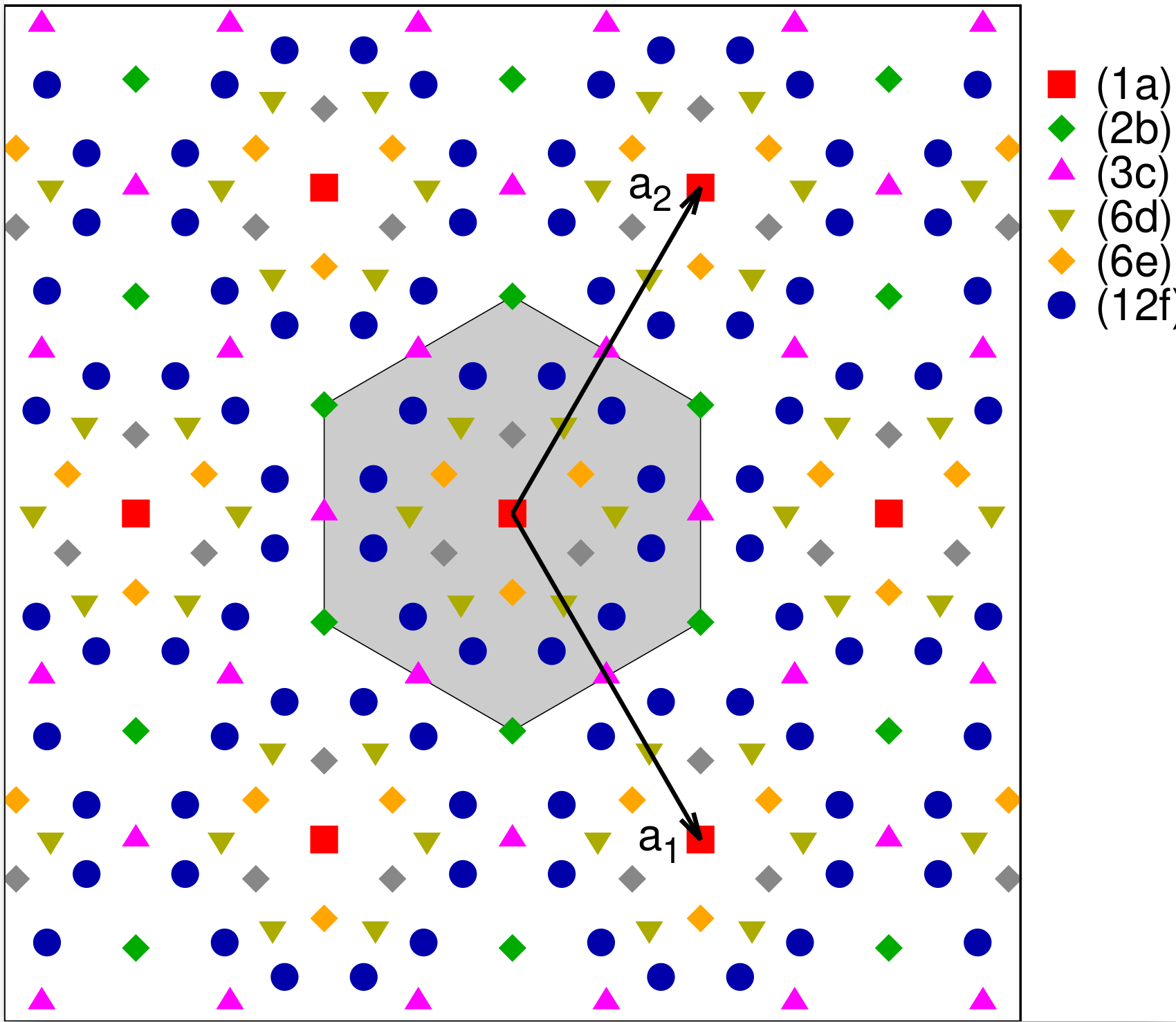

Plane Group #17: $p6mm$

The final plane group is formed by adding a mirror line along the Cartesian $\hat{x}$-axis. Along with the 6-fold rotation axis this generates a mirror line along the Cartesian $\hat{y}$-axis, as well as along the lines defined by the vectors $\pm \mathbf{a}_{1}$, $\pm \mathbf{a}_{2}$, and $\pm (\mathbf{a}_{1} + \mathbf{a}_{2})$. The Wyckoff positions for this group are given in Table 17 and a sample crystal is presented in Fig. 17.

| Label | Lattice Coordinates |

|---|---|

| (12f) | $(x,y)$ $(-y,x-y)$ $(-x+y,-x)$

$(-x,-y)$ $(y,-x+y)$ $(x-y,x)$ $(-y,-x)$ $(-x+y,y)$ $(x,x-y)$ $(y,x)$ $(x-y,y)$ $(-x,-x+y)$ |

| (6e) | $(x,-x)$ $(x,2x)$ $(-2x,-x)$

$(-x,x)$ $(-x,-2x)$ $(2x,x)$ |

| (6d) | $(x,0)$ $(0,x)$ $(-x,-x)$

$(-x,0)$ $(0,-x)$ $(x,x)$ |

| (3c) | $(1/2,0)$ $(0,1/2)$ $(1/2,1/2)$ |

| (2b) | $(1/3,2/3)$ $(2/3,1/3)$ |

| (1a) | $(0,0)$ |

The (1a), (2b) and (3c) Wyckoff positions are the same in $p6$ and $p6mm$. If a system only has atoms on these sites we will say that it has the higher symmetry, $p6mm$.

Conclusions

This concludes our study of two dimensional crystal systems. Many of the concepts discussed here will transfer into our discussion of three dimensional systems.

Further Reading

For an earlier and much more formal version of this discussion, see The Library of Crystallographic Prototypes: Part 1 2 and Part 2.3 More detail about symmetry and crystallography can also be found in Souvignier’s Group theory applied to crystallography4. The terminology we use for describing crystal class, holohedry, etc. is adapted from Lax.2 Additional information can be found in Ashcroft and Mermin5 and in all editions of Kittel.6

Glossary

Here is a brief definition of some of the terms used in this article:

- Conventional Cell

- The description of a lattice which has no translational symmetry other than that demanded by its holohedry.

- Crystal System

- The set of all lattices which have the same holohedry.

- Crystallographic Restriction Theorem

- Theorem7, 8, 9 which states that a two- or three-dimensional lattice can only have a 1-, 2-, 3-, 4-, or 6-fold rotation axis. In particular, 5-fold lattices, which would have a pentagonal Wigner-Seitz cell, are forbidden.

- Glide Line (Plane)

- A mirror line (plane in three dimensions) coupled with a translation along that line (plane).

- Holohedry

- The point group of a lattice which describes its rotational symmetry, without extra translations, mirrors, glides, or inversion. In two dimensions the only possibilities are 1-, 2-, 3-, 4-, and 6-fold rotations (rotations by 360°, 180°, 120°, 90°, and 60°, respectively) about the origin.

- Inversion Site

- A reflection of the entire crystal about a central point. This point is often taken to be the origin, but it need not be. If the inversion site is at the origin then the existence of an atom at the point $(x,y)$ implies that there is an identical atom at $(-x,-y)$. In three dimensions the points are $(x,y,x)$ and $(-x,-y,-z)$. A lattice without atoms has inversion symmetry, but when atoms are added to the system this may be destroyed.

- Mirror Line (Plane)

- A line (plane in three dimensions) about which atomic positions are reflected. That is, if the line $x=0$ is a mirror, then if there is an atom at $(x,y)$ there is another atom at $(x,-y)$. Mirror lines do not need to be along the Cartesian axis nor even pass through the origin.

- Plane Group

- A group of symmetry operations (translations, rotations, reflections, etc.) that leave a two-dimensional crystal unchanged. There are seventeen plane groups. The three dimension analog of the plane groups are the 230 space groups.

- Primitive Cell

- The description of a lattice which leads to the smallest possible Wigner-Seitz cell. If the lattice has no translational symmetry beyond that defined by its holohedry then the primitive cell is also the conventional cell.

- Standard Orientation

- The preferred orientation of the primitive vectors in a lattice. This is purely a matter of convention. You are allowed replace the “standard'' primitive vectors with any linear combinations of the primitive vectors which do not change the area of the unit cell. We will in general follow the {\AFLOW} standard convention.~\cite{curtarolo:art58}

- Wigner-Seitz Cell

- A uniquely defined unit cell consisting of all spatial points closer to a given lattice point than to any other lattice point.

- Wyckoff Positions

- Subsets of a given plane or space group, giving the positions of all the atoms which are equivalent by symmetry.

References

- M. Lax, Symmetry Principles in Solid State and Molecular Physics (J. Wiley & Sons, New York, 1974), chap. 6, pp. 169--175. Avaliable from the Internet Archive at https://archive.org/details/symmetryprincipl0000laxm.

- M. J. Mehl, D. Hicks, C. Toher, O. Levy, R. M. Hanson, G. L. W. Hart, and S. Curtarolo, The AFLOW Library of Crystallographic Prototypes: Part 1, Comput. Mater. Sci. 136, S1-S828 (2017), doi:10.1016/j.commatsci.2017.01.017.

- D. Hicks, M. J. Mehl, E. Gossett, C. Toher, O. Levy, R. M. Hanson, G. L. W. Hart, and S. Curtarolo, The AFLOW Library of Crystallographic Prototypes: Part 2, Comput. Mater. Sci. 161, S1-S1011 (2019), doi:10.1016/j.commatsci.2018.10.043.

- B. Souvignier, Group theory applied to crystallography (International Union of Crystallography, Radboud University Nijmegen, The Netherlands, 2008). https://www.math.ru.nl/~souvi/krist_09/cryst.pdf

- N. W. Ashcroft and N. D. Mermin, Solid State Physics (Saunders College Publishing, Orlando, 1976), chap. 4, pp. 73-75. Available online or as an ebook from the Internet Archive at https://archive.org/details/AshcroftSolidState.

- C. Kittel, Solid State Physics (John Wiley & Sons, New York, 1996), 7 edn. Available online or as an ebook from the Internet Archive at https://archive.org/details/IntroductionToSolidStatePhysics.

- The symmetry of crystals. The crystallographic restriction theorem, https://www.xtal.iqfr.csic.es/Cristalografia/parte_03_1_1-en.html.

- J. Bamberg, G. Cairns, and D. Kilminster, The Crystallographic Restriction, Permutations, and Goldbach's Conjecture}, American Mathematical Monthly 110, 202-209 (2003), doi:10.1080/00029890.2003.11919956.

- Crystallographic restriction theorem -- Dimensions 2 and 3, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Crystallographic_restriction_theorem#Dimensions_2_and_3.

- W. Setyawan and S. Curtarolo, High-throughput electronic band structure calculations: Challenges and tools, Comput. Mater. Sci. 49, 299-312 (2010), doi:10.1016/j.commatsci.2010.05.010.

Footnotes

† We didn't forget holohedry 3, it will be appear shortly.