Two Dimensional Periodic Systems: Part II

Lattices and Symmetries

Symmetry Operations in 2-Dimensonal Lattices

The

first

article in this series showed that lattices and crystals

have translational symmetry. That is, if we have two

non-parallel vectors $\mathbf{a}_{1}$ and $\mathbf{a}_{2}$,

then shifting the origin of the system by an amount

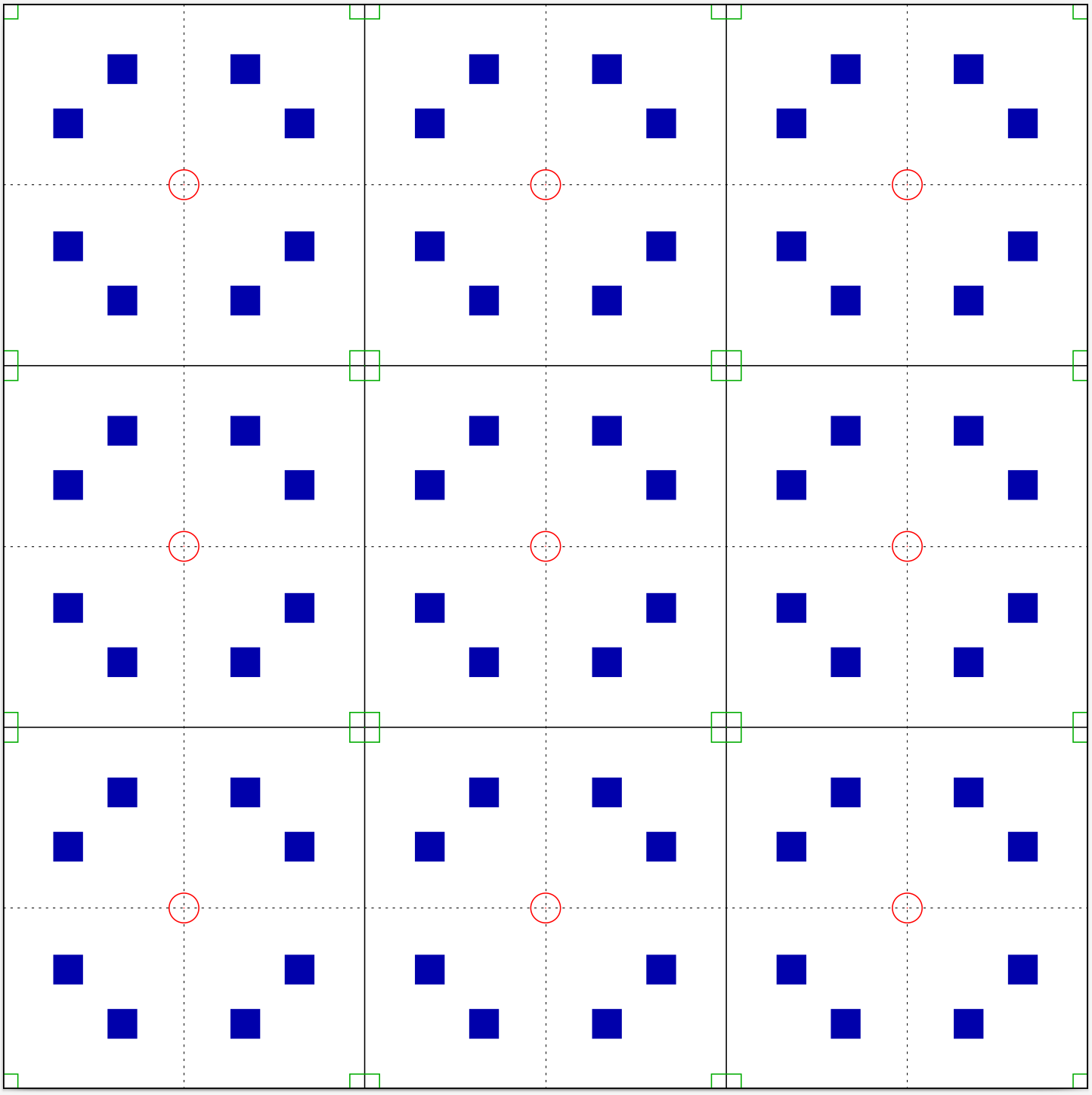

Of course crystals have more symmetry than that. As an example, look at the two-dimensional crystal in Fig. 1.

This shows a periodically repeated square lattice, with

primitive vectors

and for this figure we have arbitrarily set x = 0.17 and y = 0.32.

In addition to the translational symmetry, we see can see several other symmetries which do not change the appearance of the lattice:

- Rotation of the lattice about the center circle by 0°, 90°, 180°, or 270°. The point at the center is known as a four-fold rotation axis.

- Reflection of the atoms through the x-axis, i.e. transforming a point at (x, y) to (x, − y). In three dimensions this is called a mirror plane, and since we’re going to eventually generalize this to 3-d we’ll refer to it that way. The y-axis is another mirror plane, as are the diagonal lines y = x and y = − x.

- Inversion of the lattice through the origin: (x, y) → ( − x, − y). (We can also accomplish this by rotating by 180° around the origin, but this will not be the case in three dimensions.)

The eight (x, y) pairs form

a group.1

Wikipedia2 defines

a group is a set of elements and an operation on those

elements that is associative. One of the elements is the

identity and every element has an inverse. It’s easiest to

describe the group that generates (3)

as a set of matrices: (Don't worry, we'll only do this once)

$ I_{2} = \left( \begin{array}{cc} 0 & 1 \\ 1 & 0 \end{array} \right) , $

$ I_{3} = \left( \begin{array}{cc} 0 & -1 \\ 1 & 0 \end{array} \right) , $

$ I_{4} = \left( \begin{array}{cc} -1 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 \end{array} \right) , $ (4)

$ I_{5} = \left( \begin{array}{cc} -1 & 0 \\ 0 & -1 \end{array} \right) , $

$ I_{6} = \left( \begin{array}{cc} 0 & -1 \\ -1 & 0 \end{array} \right) , $

$ I_{7} = \left( \begin{array}{cc} 0 & 1 \\ -1 & 0 \end{array} \right) , $ and

$ I_{8} = \left( \begin{array}{cc} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & -1 \end{array} \right) , $ .

The lattice coordinates of any vector in (2) can then be generated by the transformation

The matrices (4) obviously form a group:

- The elements are the matrices.

- The operation is matrix multiplication.

- I1 is the identity.

- Every element has an inverse. For example, I3 ⋅ I7 = I1.

-

Multiplication is associative, e.g.,

$\left(I_{2} \cdot I_{3}\right) \cdot I_{4} = \left(I_{3} \cdot I_{4}\right) = I_{5}$ . (6)

- Multiplying any two matrices yields another matrix in

the group, for example,

$I_{7} \cdot I_{4} = I_{2}$ (7)

Tables of crystallographic

groups3,4 do not list

the matrices, but the consequences of the matrices. In this

case they would say

Meaning that if, say, and atom is at the point (0.1,0.2), then symmetry demands that another atom be at (0.2,0.1), (-0.1,0.2), etc.

The coordinates/operations (3), (4) or (8) form the elements of what is known as a plane group. There are seventeen possible plane groups in two dimensions. For convenience, each is given a number and a label. The current group is known as plane group #11, p4mm. The letters of the label all have meaning:

- p indicates that this is a primitive cell (more on this in the next section).

- 4 indicates a 4-fold rotation axis.

- m identifies a mirror plane, here along the x- and y-axes. We only need to specify two, because the existence of mirror planes along the axes implies the mirror planes along the diagonals.

We will discuss all seventeen groups in more detail in the next few articles, but for now let us concentrate on p4mm.

Suppose we set y = x in (3)

or (8). Then

the eight elements of the group reduce to four:

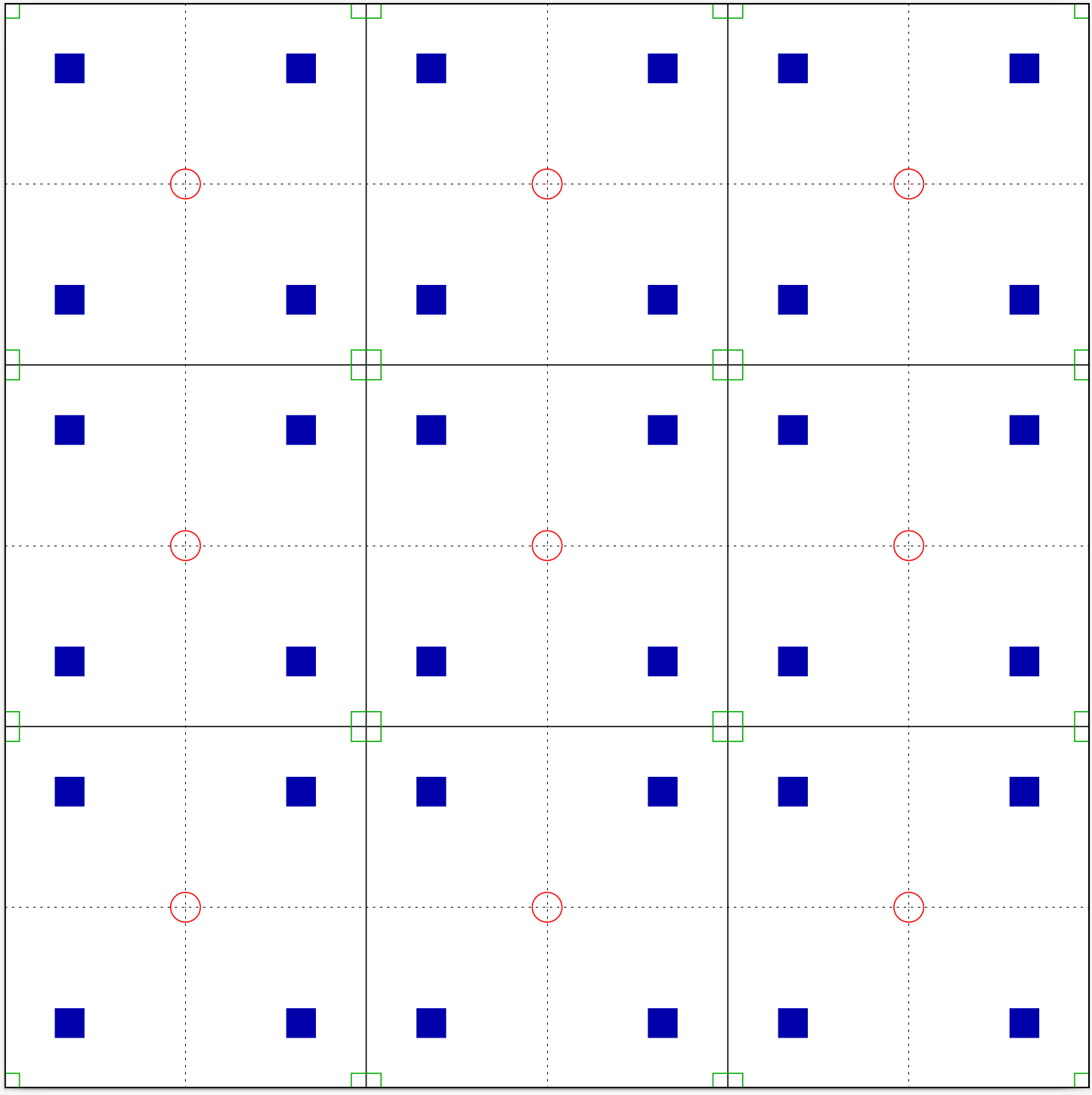

These four elements form a subgroup of p4mm, forming a group that can be derived from the elements of the original group by giving the general group coordinates specific values, in this case y = x. A crystal that only contains elements from the subgroup (9) is shown in Fig. 2.

In crystallography these subgroups are known as Wyckoff positions. They are labeled by number followed by a lower case letter, where the number is the number of sites in the subgroup, and the letter increases as the number of sites increases. The Wyckoff positions of plane group p4mm are listed in Table 1. Traditionally the positions are listed from most complex to least complex, starting with the “subgroup” which is identical to the full group.

| Label | Lattice Coordinates |

|---|---|

| (8g) | $(x,y)$ $(-x,-y)$ $(-y,x)$ $(y,-x)$ |

| $(-x,y)$ $(x,-y)$ $(y,x)$ $(-y,-x)$ | |

| (4f) | $(x,x)$ $(-x,-x)$ $(-x,x)$ $(x,-x)$ |

| (4e) | $(x,1/2)$ $(-x,1/2)$ $(1/2,x)$ $(1/2,-x)$ |

| (4d) | $(x,0)$ $(-x,0)$ $(0,x)$ $(0,-x)$ |

| (2c) | $(1/2,0)$ $(0,1/2)$ |

| (1b) | $(1/2,1/2)$ |

| (1a) | $(0,0)$ |

We see from the table that special values of x and y, here 0 and 1/2, can also generate subgroups. The open circles in Fig. 1 and Fig. 2 are on (1a) sites, and the open squares are on (1b) sites.

Finally, consider the green squares in Fig. 1 and Fig. 2. If we made one of these squares the origin, then all the operations (8) are still valid. We would just change the values of the coordinates (x, y). This is because the (1a) (red circle) and (1b) (green square) Wyckoff positions have the same site symmetry. These are the operations which preserve the crystal structure at a given site. In this case changing the origin from the red circle to the green square does not affect the overall symmetry of the crystal.

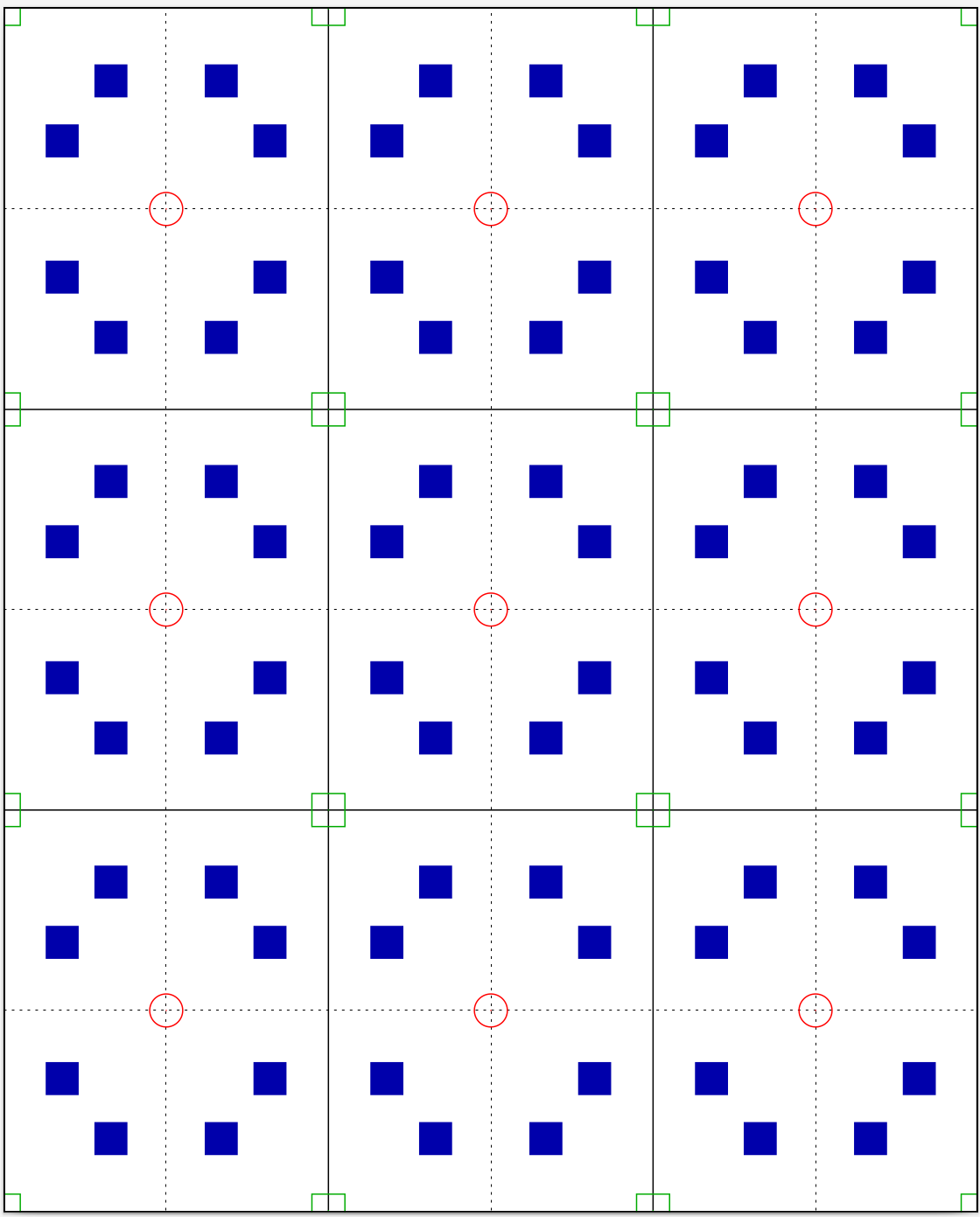

So far we have only discussed the square lattice (2). There are, of course, other possible lattices in two dimensions. If we stretch the lattice in Fig. 1 along the y-axis, we get a crystal that looks like Fig. 4.

The symmetry is obviously reduced. In particular, we no longer have a four-fold rotation axis no reflections around the y = x line. The plane group for this figure is p2mm, and its Wyckoff positions are listed in Table 2.

| Label | Lattice Coordinates |

|---|---|

| (4i) | $(x,y)$ $(-x,-y)$ $(-x,y)$ $(x,-y)$ |

| (2h) | $(1/2,y)$ $(1/2,-y)$ |

| (2g) | $(0,y)$ $(0,-y)$ |

| (2f) | $(x,1/2)$ $(-x,1/2)$ |

| (2e) | $(x,0)$ $(-x,0)$ |

| (1d) | $(1/2,1/2)$ |

| (1c) | $(1/2,0)$ |

| (1b) | $(0,1/2)$ |

| (1a) | $(0,0)$ |

There are many more Wyckoff positions here, as now the x and y coordinates do not mix. It’s also worth nothing that the blue squares now occupy two different (4i) sites.

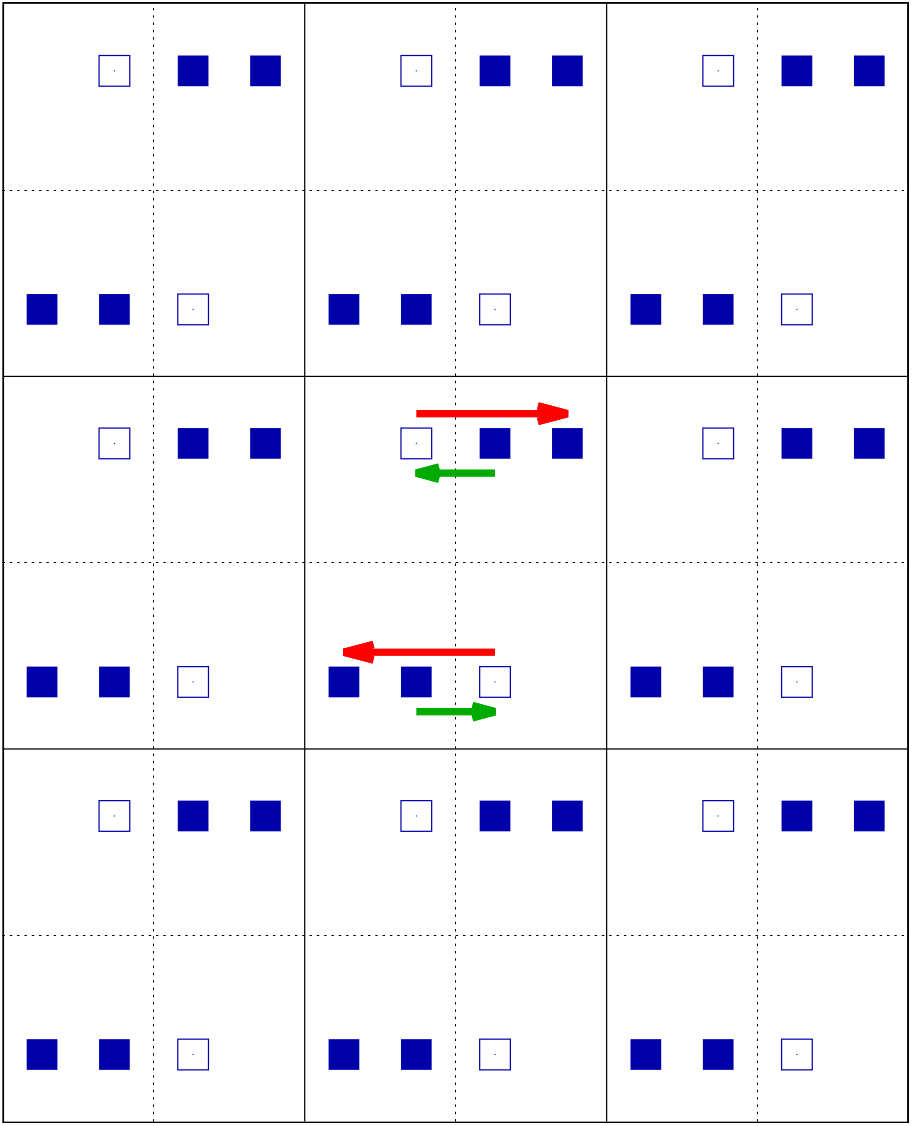

There is one more symmetry in two dimensions that we have

yet to discuss. This is the glide reflection. In a

glide reflection, we first reflect a point on the lattice

about some line, and then translate (glide) it by one-half

of a lattice vector. An example is shown in

Fig. 4. Here we

first reflect a point about the y = 0 axis

(the green arrows in the figure), and then translate it by

one-half of a lattice vector in the x direction

(the red arrows):

$(x,y) \rightarrow (-x,y) \rightarrow (1/2-x,y)$

. (10)

The resulting plane group is

labeled p2mg for obvious

reasons. Its Wyckoff positions are listed in

Table 3.

| Label | Lattice Coordinates |

|---|---|

| (4d) | $(x,y)$ $(-x,-y)$ $(-x+1/2,y)$ $(x+1/2,-y)$ |

| (2c) | $(1/4,y)$ $(3/4,-y)$ |

| (2b) | $(0,1/2)$ $(1/2,1/2)$ |

| (2a) | $(0,0)$ $(1/2,0)$ |

In the next article we’ll discuss all of the possible lattices that can exist in two dimensions. After that we’ll finally enumerate all of the seventeen plane groups available to two dimensional lattices. That finished, we will then expand on these articles to look at the three dimensional lattices.

Further Reading

For an earlier and much more formal version of this discussion, see The Library of Crystallographic Prototypes: Part 25. More detail about symmetry and crystallography can also be found in Souvignier’s Group theory applied to crystallography1.

Glossary

Here is a brief definition of some of the terms used in this article:

- Glide Reflection

- A reflection, such as x → − x, followed by a translation (glide) of one-half a lattice vector.

- Group

- A set of elements connected by an operation. In a crystal, the elements are the transformations that move an atom from one place to another in the crystal, and the operation generates all the elements. A group must have an identity element, and every member of the group must have an inverse.

- Plane Group

- A group which lists possible symmetry elements that leave a two-dimensional crystal unchanged. There are seventeen plane groups. The three dimension analog of the plane groups are the 230 space groups.

- Site Symmetry

- The rotational, mirror, and inversion symmetries around a given site in a lattice.

- Wigner-Seitz Cell

- A uniquely defined unit cell consisting of all spatial points closer to a given lattice point than to any other lattice point.

- Wyckoff Positions

- Subgroups of a given plane or space group.

References

- B. Souvignier, Group theory applied to crystallography (International Union of Crystallography, Radboud University Nijmegen, The Netherlands, 2008). https://www.math.ru.nl/~souvi/krist_09/cryst.pdf

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Group_(mathematics).

- T. Hahn, ed., International Tables of Crystallography. Volume A: Spacegroup symmetry (Kluwer Academic publishers, International Union of Crystallography, Chester, England, 2002).

- M. I. Aroyo, J. M. Perez-Mato, C. Capillas, E. Kroumova, S. Ivantchev, G. Madariaga, A. Kirov, and H. Wondratschek, Bilbao Crystallographic Server: I. Databases and crystallographic computing programs, Z. Krystallogr. 221, 15–27 (2006), doi:10.1524/zkri.2006.221.1.15. Website: https://www.cryst.ehu.es/.

- D. Hicks, M. J. Mehl, E. Gossett, C. Toher, O. Levy, R. M. Hanson, G. L. W. Hart, and S. Curtarolo, The AFLOW Library of Crystallographic Prototypes: Part 2, Comput. Mater. Sci. 161, S1–S1011 (2019), doi:10.1016/j.commatsci.2018.10.043.

- J. Bamberg, G. Cairns, and D. Kilminster, The Crystallographic Restriction, Permutations, and Goldbach’s Conjecture, American Mathematical Monthly 110, 202–209 (2003), doi:10.1080/00029890.2003.11919956.