Two Dimensional Periodic Systems: Part III

Possible Two Dimensonal Lattices

In the previous article we discussed the general problem of lattices and translational symmetry in two dimensions. We did not consider other symmetries possible in two dimensions: rotations, mirroring, and inversions.

Here we'll discuss the possible lattices that can be drawn in two dimensions. We'll see that they are limited by the requirements of translational and rotational symmetry. The next article will put it all together and look at the full set of symmetries available in two dimensions, and list all of the Wyckoff positions for each of the seventeen plane groups.

Let's start by dividing the possible lattices by their rotational symmetry. That is, we'll rotate the lattice around its origin and see how far we can get before we recover the original lattice. In general that will be some value 360°/$n$, where $n$ is an integer. Obviously this implies that rotations $m$ × 360°/$n$ also reproduce the lattice, so we say such a lattice has n-fold rotation symmetry, or a holohedry of $n$.† All lattices with the same holohedry from a Crystal System. Given that, we'll list the lattices in increasing order of $n$.

Parallelogram Crystal System (Holohedry 1)

The Parallelogram

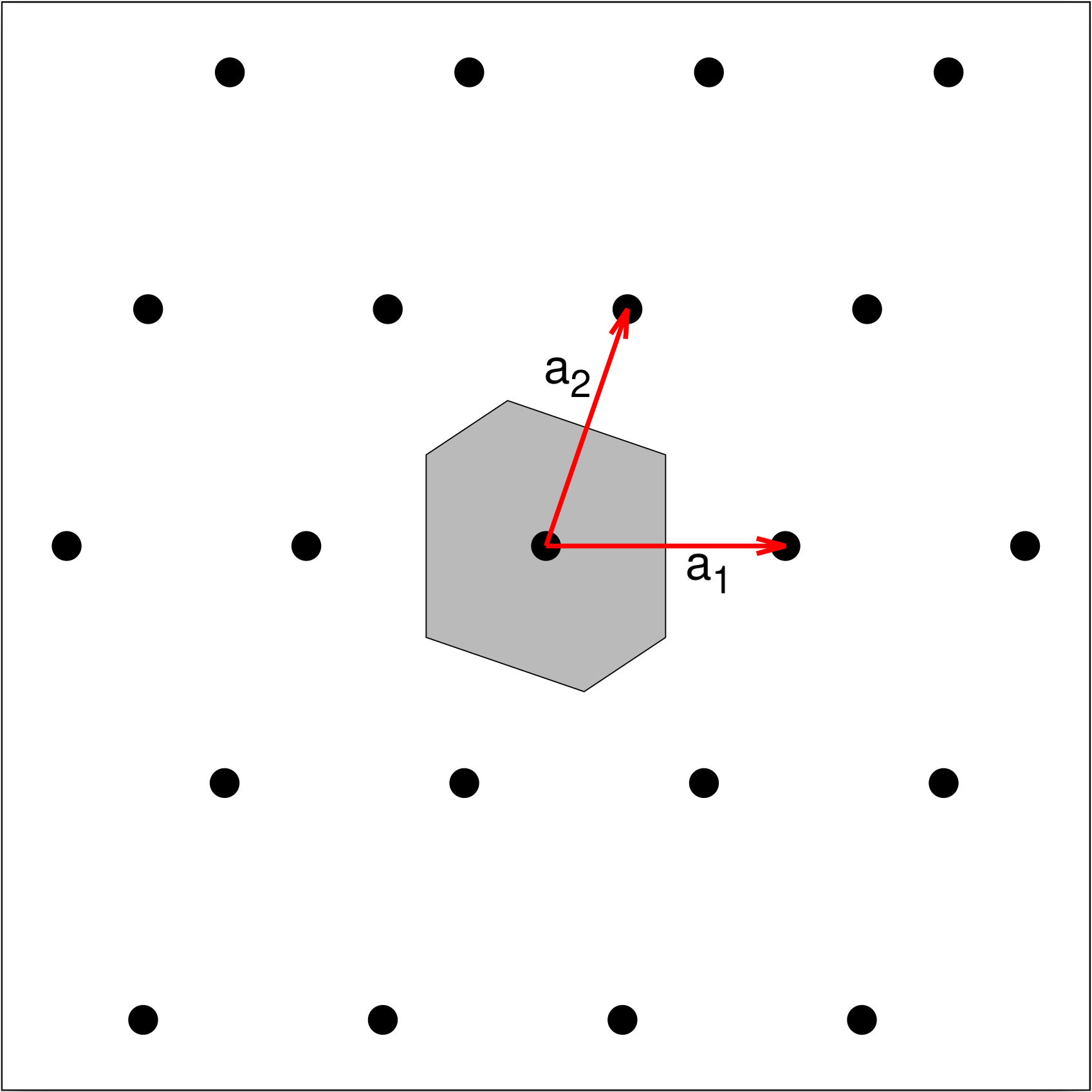

The most general lattice in two dimensions, called rather unimaginatively the parallelogram, is shown in Fig. 1. We've chosen to align the lattice in a standard orientation, with the primitive vector $\mathbf{a}_{1}$ aligned along the x-axis:

Every lattice in two dimensions can be placed in the form (1), but we will reserve this name for a lattice that does not have a higher rotational symmetry. This means that we'll call a lattice a parallelogram if and only if:

Certain linear combinations of primitive vectors can also move the lattice to a higher symmetry, e.g.,

Fig. 1 also shows the Wigner-Seitz cell for the lattice. The rather distorted hexagon is a characteristic of the general parallelogram lattice.

Rectangular Crystal System (Holohedry 2)

There are two lattices which have 2-fold rotation symmetry, the rectangular lattice and the “centered” rectangular lattice.

The Rectangular Lattice

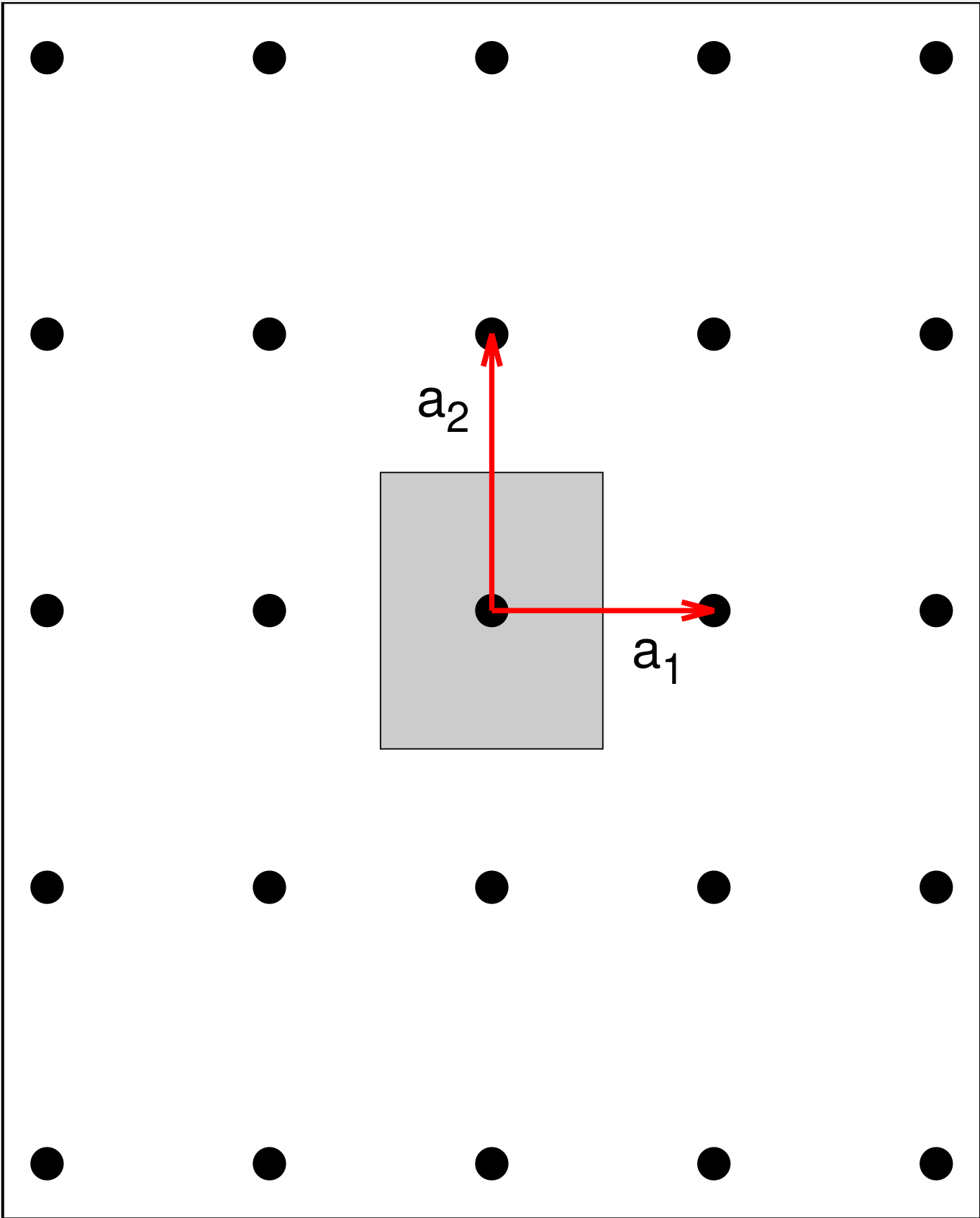

A simple rectangular lattice is shown in Fig. 2, along with its Wigner-Seitz cell. As you might guess, the lattice is defined by the conditions

In our standard orientation, the primitive vectors of this lattice are

The Centered Rectangular Lattice

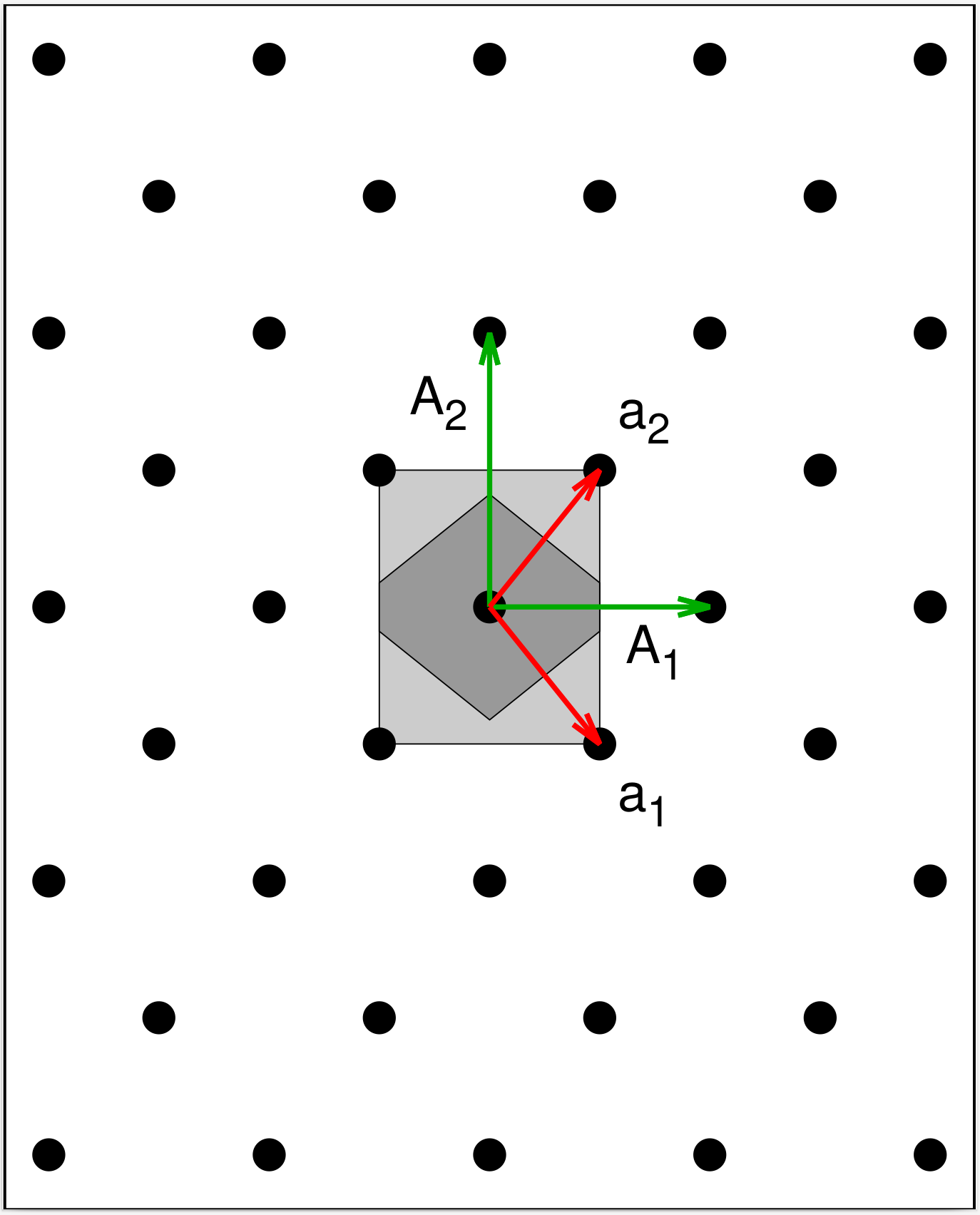

Now consider the lattice in Fig. 3. It it is identical to the one in Fig. 2 except for the spots added in the middle of each rectangle. As such, this is a rectangular system with additional translational symmetry. The primitive vectors of the lattice (in our standard notation) are

Just as with the parallelogram there are special cases when this system is kicked up to a higher rotational symmetry. These are

Although (11) is the most compact way of defining the lattice, it is often useful to explicitly refer to its underlying rectangular nature. To this end we define the conventional lattice, with “primitive” vectors

Crystallographers ordinarily give positions in terms of the conventional lattice rather than the primitive lattice. This seems confusing until we realize that (11) is not a unique way to define the primitive centered lattice. We could just as easily have picked

Trigonal Crystal System (Holohedry 3)

As we will see below, a lattice with 3-fold rotational symmetry will also have 6-fold rotational symmetry, so we will postpone this discussion until we get to $n = 6$.

Square Crystal System (Holohedry 4)

The Square Lattice

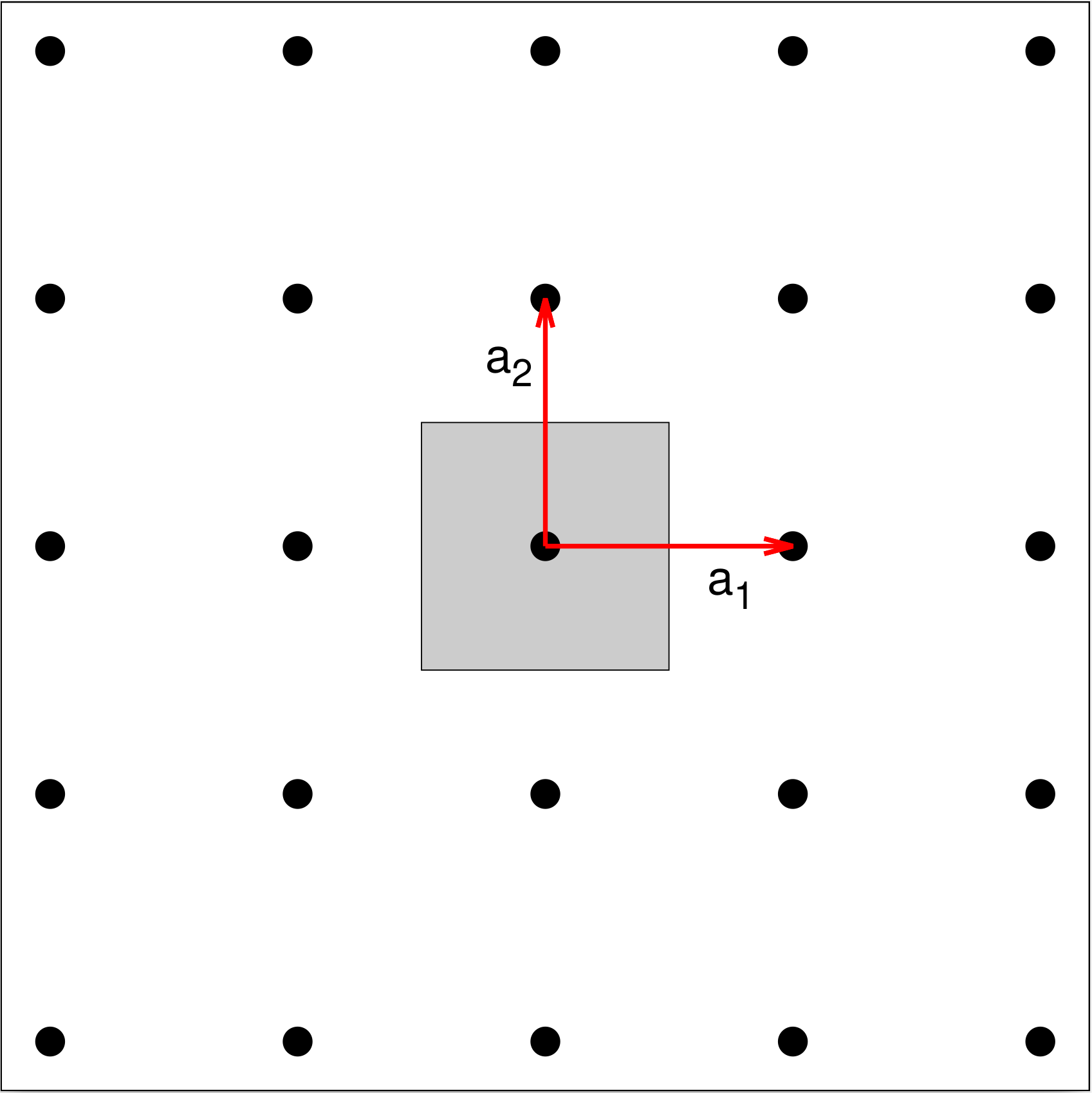

This is perhaps the simplest lattice: the primitive vectors are orthogonal to one another and equal in length:

5-fold Rotational Symmetry (Holohedry 5)

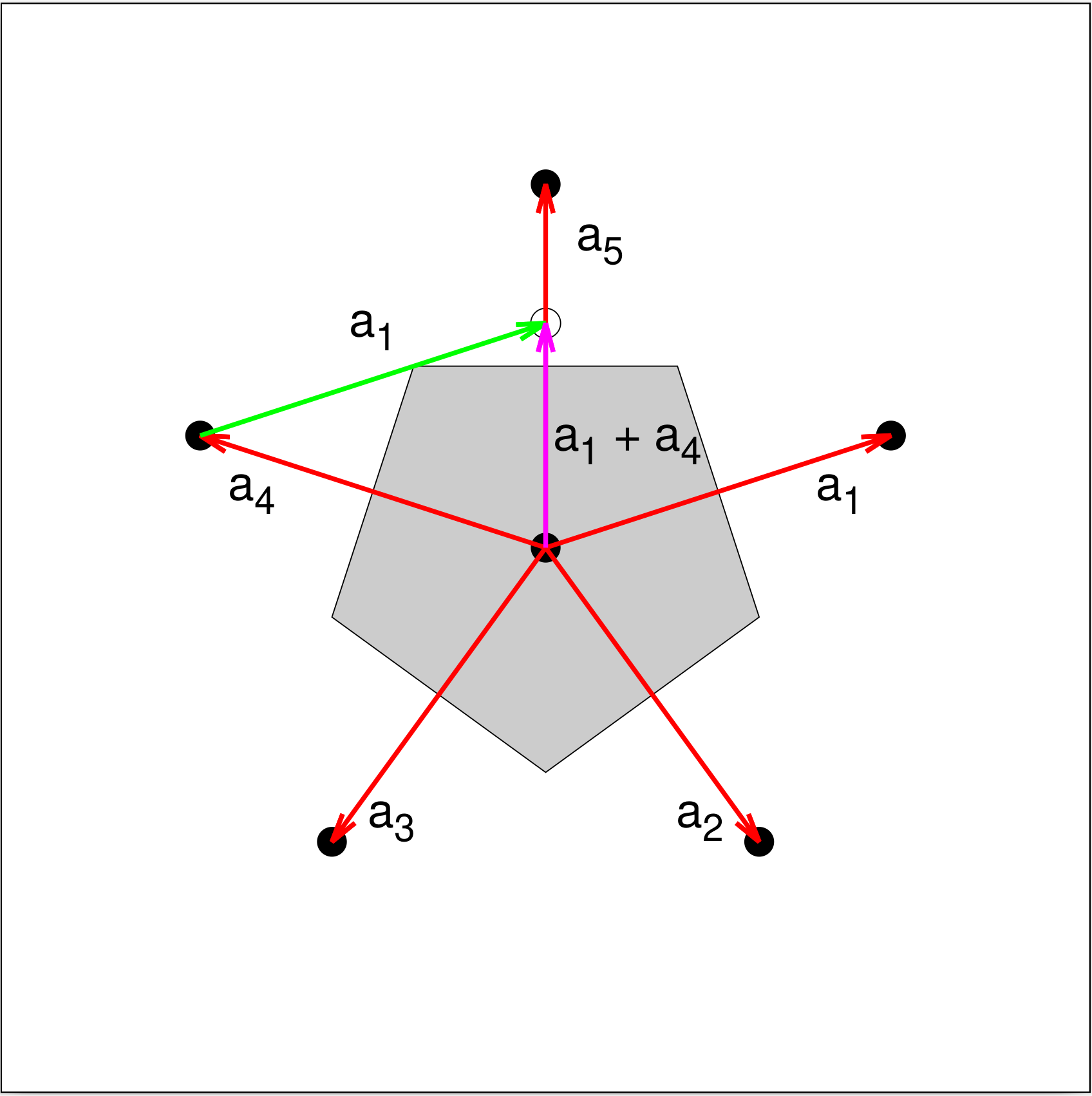

While quasicrystals3 show five-fold rotational symmetry, they are not true crystals, as they do not have translational symmetry. This can be seen in \reffig{fig:pentagon}. Here we show six points in a hypothetical lattice with a 5-fold rotation axis. The vectors $\mathbf{a}_{1}$ through $\mathbf{a}_{5}$ are candidate lattice vectors. If we arbitrarily pick $\mathbf{a}_{1}$ and $\mathbf{a}_{4}$ as our primitive vectors, then we should be able to write all of the $\mathbf{a}_{i}$ in the form

This is a specific case of the Crystallographic restriction theorem, which states that two- and three-dimensional lattices can only have 1-, 2-, 3-, 4- and 6-fold rotation axis. Bamberg et al.4 prove the theorem for all dimensions, but Wikipedia5 has a much more understandable proof for two and three dimensions.

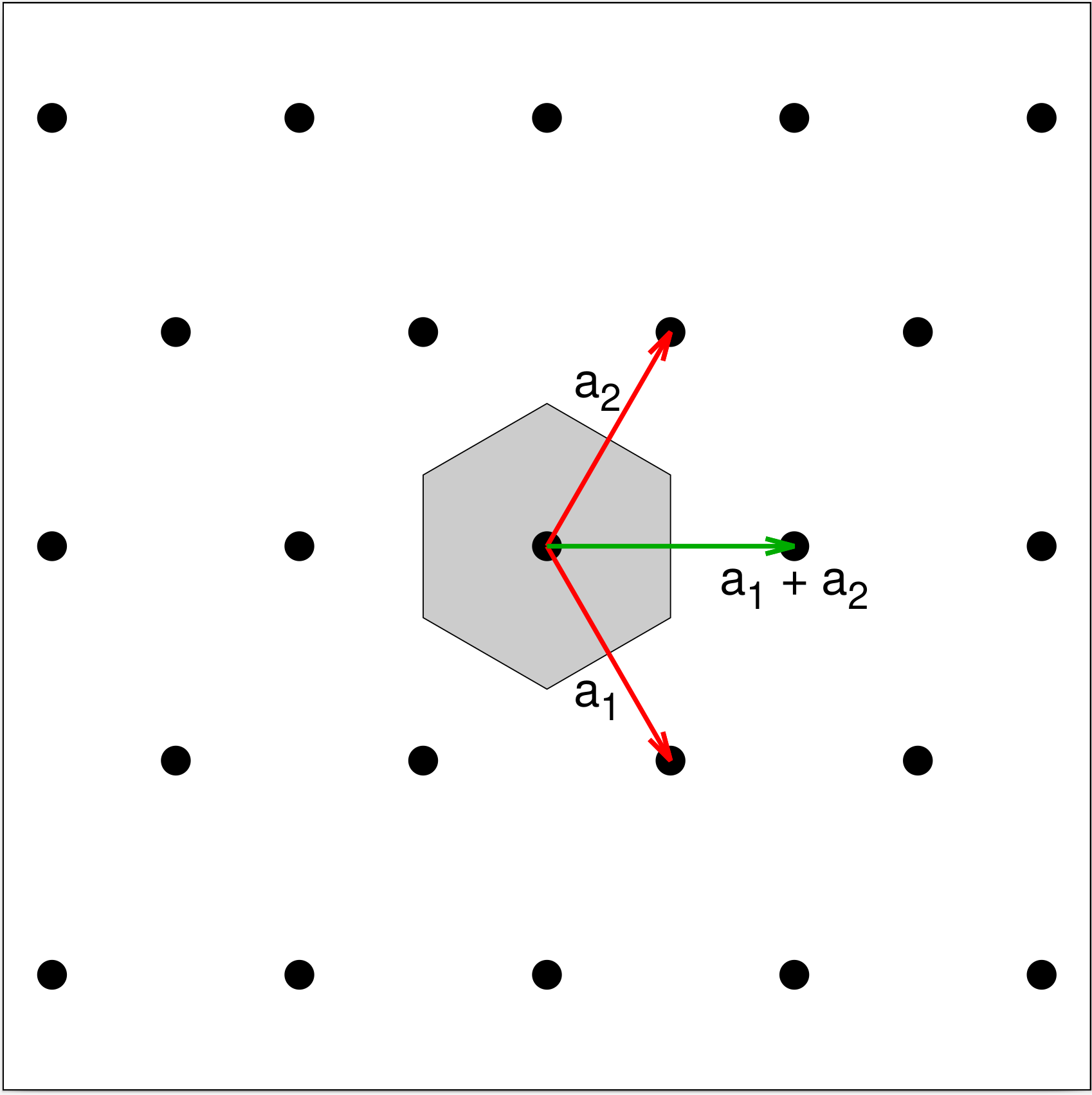

Hexagonal Crystal System (Holohedry 6)

The Hexagonal Lattice

If we set $b = \sqrt{3} a$ in the centered rectangular lattice (11) we find the primitive vectors

The reciprocal lattice vectors associated with (23) are

Since the hexagonal lattice is an offshoot of the centered rectangular lattice, you might think that lattice coordinates would be given in terms of the corresponding “conventional” unit cell as in (16) with $b = \sqrt{3}a$. This turns out not to be the case. Lattice coordinates $(x,y)$ are always given in terms of the vectors (23):

This concludes our enumeration of the possible two dimensional lattices. Next we'll decorate those lattices with “atoms” and see what kinds of symmetries are available to us.

Further Reading

For an earlier and much more formal version of this discussion, see The Library of Crystallographic Prototypes: Part 2.5 More detail about symmetry and crystallography can also be found in Souvignier’s Group theory applied to crystallography1 and Lax's Symmetry Principles in Solid State and Molecular Physics2.

Glossary

Here is a brief definition of some of the terms used in this article:

- Crystal Class

- The set of all lattices which have the same holohedry.

- Crystallographic Restriction Theorem

- Theorem2, 4, 5 which states that a two- or three-dimensional lattice can only have a 1-, 2-, 3-, 4-, or 6-fold rotation axis. In particular, 5-fold lattices, which would have a pentagonal Wigner-Seitz cell, are forbidden.

- Holohedry

- The point group of a lattice which describes its rotational symmetry, without translations, mirrors, glides, or inversion. In two dimensions the only possibilities are 1-, 2-, 3-, 4-, and 6-fold rotations (rotations by 360°, 180°, 120°, 90°, and 60°, respectively) about the origin.

- n-fold Rotation Axis

- A rotation of the crystal by 360°/n which replicates the original crystal. The only allowed values of n are 1, 2, 3, 4, and 6.

- Plane Group

- A group which lists possible symmetry elements that leave a two-dimensional crystal unchanged. There are seventeen plane groups. The three dimension analog of the plane groups are the 230 space groups.

- Quasicrystal

- A solid which exhibits a 5-fold (icosahedral) rotational symmetry.3 It is not a crystal, as it does not exhibit translational symmetry or long-range order. See the Crystallographic Restriction Theorem.

- Standard Orientation

- The preferred orientation of the primitive vectors in a lattice. This is purely a matter of convention. You are allowed replace the “standard” primitive vectors with any linear combinations of the primitive vectors which do not change the area of the unit cell. We will in general follow the {\AFLOW} standard convention.8

- Wigner-Seitz Cell

- A uniquely defined unit cell consisting of all spatial points closer to a given lattice point than to any other lattice point.

- Wyckoff Positions

- Subsets of a given plane or space group.

References

- M. Lax, Symmetry Principles in Solid State and Molecular Physics (J. Wiley & Sons, New York, 1974), chap. 6, pp. 169–175. Avaliable from the Internet Archive at https://archive.org/details/symmetryprincipl0000laxm

- The symmetry of crystals. The crystallographic restriction theorem. https://www.xtal.iqfr.csic.es/Cristalografia/parte_03_1_1-en.html.

- W. Steurer, Quasicrystals: What do we know? What do we want to know? What can we know?, Acta Crystallographica A 74, 1–11 (2018), doi:10.1107/S2053273317016540.

- J. Bamberg, G. Cairns, and D. Kilminster, The Crystallographic Restriction, Permutations, and Goldbach’s Conjecture, American Mathematical Monthly 110, 202–209 (2003), doi:10.1080/00029890.2003.11919956.

- Crystallographic restriction theorem – Dimensions 2 and 3. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Crystallographic_restriction_theorem#Dimensions_2_and_3.

- D. Hicks, M. J. Mehl, E. Gossett, C. Toher, O. Levy, R. M. Hanson, G. L. W. Hart, and S. Curtarolo, The AFLOW Library of Crystallographic Prototypes: Part 2, Comput. Mater. Sci. 161, S1–S1011 (2019), doi:10.1016/j.commatsci.2018.10.043.

- B. Souvignier, Group theory applied to crystallography (International Union of Crystallography, Radboud University Nijmegen, The Netherlands, 2008). https://www.math.ru.nl/~souvi/krist_09/cryst.pdf

- W. Setyawan and S. Curtarolo, High-throughput electronic band structure calculations: Challenges and tools, Comput. Mater. Sci. 49, 299–312 (2010), doi:10.1016/j.commatsci.2010.05.010.

Footnotes

†It is not really proper to designate the holohedry of the system by its rotations,1 but it is sufficient in two dimensions. We'll address the three dimensional case in another article.